Bhatra: Difference between revisions

Kingsingh13 (talk | contribs) (addition of introduction) |

Kingsingh13 (talk | contribs) (addition of sikhism) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

The Bhatra/Bhat Sikhs were originally northern hindu [[Saraswat Brahmin]]s who eventually became Sikhs, these Brahmins were [[Autochthon (person)|autochthonous]] inhabitants who helped found the Indus-Saraswati civilization during 4000-2000BC. They lived in the 700+ archeological sites discovered along the former [[Sarasvati River|Saraswati River]] that once flowed parallel to the [[Indus]] in present day Kashmir, Himachal, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan regions. As the intellectual and priestly class of that ancient civilization, they are highly respected and honored for creating the world's oldest literary and religious traditions. They were the original propagators (some argue composers too) of the revered texts such as the Vedas and the Upanishads and took these texts into other parts of South Asia. They are considered to be the descendants of the revered Brahmin, ''Sage Saraswat Muni,'' who lived on the banks of the ancient river Saraswati.<ref name=kaw>{{cite book|first1=M.K. |last1=Kaw |title=Kashmiri Pandits: Looking to the future |url=http://books.google.co.th/books?id=VMM-xRVr5qgC&pg=PA35&lpg=PA35&dq=kashmiri+pandits+saraswat+brahmins&source=bl&ots=2DzIpkFhQn&sig=l2muBsQVSQgeQyC3zJILTwDWdLw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=aAH3T5bTMo3rrQe20IHUBg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=kashmiri%20pandits%20saraswat%20brahmins&f=false |accessdate=7 July 2012|year=2008|publisher=APH Publishing House |location=5, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi |isbn= 8176482366 |page=32}}</ref> Around 1900 BC, the river Saraswati started vanishing under ground and the people on its banks started migrating to other parts of South Asia thus forming sub-communities. | The Bhatra/Bhat Sikhs were originally northern hindu [[Saraswat Brahmin]]s who eventually became Sikhs, these Brahmins were [[Autochthon (person)|autochthonous]] inhabitants who helped found the Indus-Saraswati civilization during 4000-2000BC. They lived in the 700+ archeological sites discovered along the former [[Sarasvati River|Saraswati River]] that once flowed parallel to the [[Indus]] in present day Kashmir, Himachal, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan regions. As the intellectual and priestly class of that ancient civilization, they are highly respected and honored for creating the world's oldest literary and religious traditions. They were the original propagators (some argue composers too) of the revered texts such as the Vedas and the Upanishads and took these texts into other parts of South Asia. They are considered to be the descendants of the revered Brahmin, ''Sage Saraswat Muni,'' who lived on the banks of the ancient river Saraswati.<ref name=kaw>{{cite book|first1=M.K. |last1=Kaw |title=Kashmiri Pandits: Looking to the future |url=http://books.google.co.th/books?id=VMM-xRVr5qgC&pg=PA35&lpg=PA35&dq=kashmiri+pandits+saraswat+brahmins&source=bl&ots=2DzIpkFhQn&sig=l2muBsQVSQgeQyC3zJILTwDWdLw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=aAH3T5bTMo3rrQe20IHUBg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=kashmiri%20pandits%20saraswat%20brahmins&f=false |accessdate=7 July 2012|year=2008|publisher=APH Publishing House |location=5, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi |isbn= 8176482366 |page=32}}</ref> Around 1900 BC, the river Saraswati started vanishing under ground and the people on its banks started migrating to other parts of South Asia thus forming sub-communities. | ||

During the Islamic invasions of modern day Pakistan and india, many Saraswat Brahmins were forced to flee due to religious oppression. Such as the saraswat Brahmin [[Kashmiri Pandit]]. | During the Islamic invasions of modern day Pakistan and india, many Saraswat Brahmins were forced to flee due to religious oppression. Such as the saraswat Brahmin [[Kashmiri Pandit]]. | ||

===Religious Oppression=== | |||

An estimate of the number of people killed, based on the Muslim chronicles and demographic calculations, was done by [[K.S. Lal]] in his book ''[[Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India]]'', who claimed that between 1000 CE and 1500 CE, the population of Hindus decreased by 80 million. | |||

[[Sir Jadunath Sarkar]] contends that that several Muslim invaders were waging a systematic [[jihad]] against Hindus in India to the effect that "Every device short of massacre in cold blood was resorted to in order to convert heathen subjects."<ref>{{cite book |last=Sarkar |first= Jadunath |authorlink=Jadunath Sarkar |title=How the Muslims forcibly converted the Hindus of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to Islam }}</ref> In particular the records kept by al-Utbi, Mahmud al-Ghazni's secretary, in the Tarikh-i-Yamini document several episodes of bloody military campaigns.<ref name="history of india">{{cite book |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924073036729#page/n39/mode/2up |title=The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period|author=Sir H. M. Elliot |chapter=Chapter II, Tarikh Yamini or Kitabu-l Yamini by Al Utbi |pages=14–52 |publisher=Trubner and Co |year=1869 }}</ref> | |||

In the early 11th century, [[Mahmud of Ghazni]] launched seventeen expeditions into South Asia. In 1001, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni defeated Raja [[Jayapala]] of the [[Hindu Shahi]] Dynasty of [[Gandhara]], the [[Battle of Peshawar (1001)|Battle of Peshawar]] and marched further into [[Peshawar]] and, in 1005, made it the center for his forces. | |||

The Ghaznavid conquests were initially directed against the [[Ismaili]] [[Fatimid]]s of [[Multan]], who were engaged in an on-going struggle with the [[Abbasid Caliphate]] in conjunction with their compatriots of the [[Fatimid Caliphate]] in North Africa and the Middle East; Mahmud apparently hoped to curry the favor of the Abbasids in this fashion. However, once this aim was accomplished, he moved onto the richness of the loot of wealthy temples and monasteries. By 1027, Mahmud had captured parts of North India and obtained formal recognition of Ghazni's sovereignty from the Abbassid Caliph, [[al-Qadir]] Billah. | |||

Ghaznavid rule in Northwestern India lasted over 175 years, from 1010 to 1187. It was during this period that [[Lahore]] assumed considerable importance apart from being the second capital, and later the only capital, of the [[Ghaznavid Empire]]. | |||

At the end of his reign, Mahmud's empire extended from [[Kurdistan]] in the west to [[Samarkand]] in the Northeast, and from the [[Caspian Sea]] to the [[Punjab region|Punjab]]. Although his raids carried his forces across Northern and Western India, only Punjab came under his permanent rule; [[Kashmir]], the [[Doab]], [[Rajasthan]], and [[Gujarat]] remained under the control of the local [[Rajput]] dynasties. | |||

The Sultan's army was easily defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins. Before the battle for Delhi, Timur executed more than 100,000 [[Hindu]] captives.<ref name=EI>Cahen, Cl.; İnalcık, Halil; Hardy, P. "Ḏj̲izzya." ''Encyclopaedia of Islam''. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 29 April 2008</ref> | |||

<ref name="EI"/><ref name="taimur">[http://persian.packhum.org/persian/index.jsp?serv=pf&file=80201010&ct=0 Volume III: To the Year A.D. 1398, Chapter: XVIII. Malfúzát-i Tímúrí, or Túzak-i Tímúrí: The Autobiography or Memoirs of Emperor Tímúr (Taimur the lame). Page: 389] ([http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201013&ct=97 1. Online copy], [http://www.infinityfoundation.com/mandala/h_es/h_es_malfuzat_frameset.htm 2. Online copy]) from: Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. [[The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period]]; London Trubner Company 1867–1877.)</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=History of India |first=Stanley |last=Lane-Poole |year=1907 |publisher=The Grolier Society |chapter=Chapter IX: Tinur's Account of His Invasion }} {{google books|4a1jSn1oQxkC|Full text}}</ref> Timur's purported autobiography, the ''Tuzk-e-Taimuri'' ("Memoirs of Temur") is a later fabrication, although most of the historical facts are accurate.<ref>B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam.</ref> | |||

As per Malfuzat-i-Timuri,<ref name="taimur" /> Timur targeted Hindus. In his own words, "Excepting the quarter of the saiyids, the 'ulama and the other Musalmans [sic], the whole city was sacked". In his descriptions of the Loni massacre he wrote, "..Next day I gave orders that the Musalman prisoners should be separated and saved." During the ransacking of Delhi, almost all inhabitants not killed were [[POW|captured]] and [[slavery|enslaved]]. | |||

Timur's memoirs on his invasion of India describe in detail the massacre of Hindus, looting plundering and raping of their women and children, their forced conversions to Islam and the plunder of the wealth of [[Hindustan]] ([[Greater India]]). It gives details of how villages, towns and entire cities were rid of their Hindu male population through systematic mass slaughters and [[genocide]] and their women and children forcefully converted en masse to Islam from Hinduism. | |||

Up to about the beginning of the 13th century, Islam became the dominant religion in Kashmir as a large number of Saraswat Kashmiri Pandits were converted to Islam. | |||

Mahmud's armies looted temples in [[Varanasi]], [[Mathura]], [[Ujjain]], [[Maheshwar]], Jwalamukhi, [[Somnath]] and [[Dwarka]]. | |||

The [[Sayyid]] (1414–51), and the [[Lodhi]] (1451–1526). Muslim Kings extended their domains into Southern India, Kingdom of Vijayanagar resisted until falling to the Deccan Sultanate in 1565. Certain kingdoms remained independent of Delhi such as the larger kingdoms of [[Punjab, India|Punjab]], [[Rajasthan]], parts of the [[Deccan]], Gujarat, [[Malwa]] (central India), and [[Bengal]], nevertheless all of the area in present-day Pakistan came under the rule of Delhi. | |||

The Sultans of Delhi enjoyed cordial, if superficial, relations with Muslim rulers in the Near East but owed them no allegiance. They based their laws on the ''[[Quran]]'' and the ''[[sharia]]'' and permitted non-Muslim subjects to practice their religion only if they paid the ''[[jizya]]'' (poll tax). They ruled from urban centres, while military camps and trading posts provided the nuclei for towns that sprang up in the countryside. | |||

===Sikhism=== | |||

The destruction of [[Hindu]] temples in [[India]] during the [[Islamic conquest of India]] occurred from the beginning of Muslim conquest until the end the [[Mughal Empire]] throughout the [[Indian subcontinent]]. In the book "[[Hindu Temples - What Happened to Them]]", Sita Ram Goel produced a politically contentious list of 2000 mosques that it is claimed were built on Hindu temples.<ref name="jb">[http://www.scribd.com/doc/10120488/Hindu-TemplesWhat-Happend-to-Them-by-Sita-Ram-Goel] Hindu temples- What happened to them</ref> During the 14th to 16th century many Saraswat Brahmins were forced to lead unsettled lifes, unable to practice their hereditary profession as Hindu priests, artists, teachers, scribes, technicians class (varna). They used their academia in there unsettled life travelling as scribes, genealogies, bards and astrologists. In the 15th century the religion of Sikhism was born causing many to follow the word of Guru Nanak Dev Ji. Further conversions of the Saraswat Brahmins Bhats to Sikhism were induced by a royal preacher by the name of Prince Baba Changa Bhat Rai. | |||

Bhat/Bhatra tradition and Sikh text states their ancestors came from [[Punjab region|Punjab]], where the Raja Shivnabh and his kingdom became the original 16th century followers of [[Guru Nanak]], the founder of Sikhism. The Raja's grandson Prince Baba Changa after studying and competing in competition for 14 years under the high Pandit Chetan Gir earned the title ‘Bhat Rai’ – the ‘Raja of Poets, and then settled himself and his followers all over India as missionaries to spread the word of Guru Nanak, where most of northern Saraswat Brahmin Bhat became Bhat Sikhs. The Bhats also contributed 123 compositions in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib (pp.1389–1409), known as the "Bhata de Savaiyye".<ref>[http://www.bhatra.co.uk]</ref> They also wrote the [[Bhat Vahis]], which were scrolls or records on the Gurus and Sikhism maintained by the Bhat Sikhs. As Guru Nanak and Sikhism do not support the caste system, the Bhat people do not consider themselves as a caste in the typical sense due to the message of Guru Nanak, but a clan within [[Sikhism]] linked by Guru Nanak which is not shackled by the caste system. The majority were from the northern [[Saraswat Brahmin]] caste ([[Bhat clan]]),([[Bhat (surname)]]) as the Prince Baba Changa Bhat Rai although a [[kshatriya]], trained under Brahmins scholars and shared the Bhat [[Brahmin]] heritage due to his passion for religion, many continued to be called the Bhat/Bhat-rai sikhs, eventually leading to the name Bhat-ra Sikh. The sangat also had many members from different areas of the Sikh caste spectrum, such as the Hindu Rajputs and Hindu Jats who joined due to Bhat sikh missionary efforts. The [[Ramaiya]] community of [[Uttar Pradesh]] is said to be a sub-clan of Bhatra origin.<ref>Sikh Encyclopedia</ref> Currently there are many Hindus and Muslims that share the Brahmin Bhat heritage.<ref>[^ http://books.google.com.pk/books?id=QpjKpK7ywPIC&pg=PA365&lpg=PA365&dq=History+of+kashmir+and+its+people&source=bl&ots=-RI_8tLrab&sig=8d9tzPeeB5lAjaq9RZqzYO8QydA&hl=en&ei=ab9pSobcB46PkAXutZW4Cw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6]</ref> Today modern Bhat sikhs are commonly known to have pioneered many of the first Gurdwaras outside of India and have donated to various Gurdwaras. | |||

[[File:Bhai Mati Das.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Sacrifice of Bhai Mati Das for the Sikh faith, being brutually killed by the Mughals, this image is from a Sikh History museum being run single handedly by one person in a small tin shed on way from Mohali to Sirhind in Punjab, India]] | |||

In the 17th century Bhats Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das were Saraswat [[Mohyal]] [[Brahmin]]<ref>{{cite book | title = The Great Gurus of the Sikhs | author = O. P. Ralhan | year = 1997 | page = 16 | isbn = 978-81-7488-479-4 | publisher = Anmol Publications | quote = His life-long companion Bhai Mati Das, a Mohyal Brahmin of village Karyala in Jehlam district...}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | title = History of the Sikhs | author = Hari Ram Gupta - Sikhs | year = 1978 | publisher = Munshiram Manoharlal | page = 211 | quote = The Guru's companions included Mati Das, a Mohyal Brahmin...}}</ref> and were disciples of the ninth Sikh Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675). They were executed along with the Guru at the Kotwali (police-station) near the Sunehri Masjid in the Chandni Chowk area of Old Delhi, under the express orders of emperor Aurangzeb. Bhat Bhai Sati Das was wrapped in cotton wool and set on fire by the Mughal authorities for refusing to denounce his faith. His brother Bhat Bhai Mati Das was also tortured to death, by having his head sawn in two. | |||

On 16 December 1634 the Sikh forces under the command of Rai Jodh and Kirt Bhat waged a guerrilla attack on Mughal forces at night, whereby the Sikhs routed and defeated the enemy. Guru Sahib lost 1200 Saint Soldiers including Kirat Bhat Ji. On the other side Sameer Beg and his two sons Shams Beg and Qasim Beg were also killed. The Mughal forces fled to Lahore leaving behind the dead and wounded. | |||

After the Battle of Kartarpur, Guru Hargobind Sahib moved towards Kiratpur Sahib, which was under the rule of Raja Tara Chand (a hill state chief). Guru Sahib's entourage was suddenly ambushed by a contingent of royal forces under the command of Ahmed Khan in the village Palahi near Phagwara town on 29 April 1635. It caused considerable loss on the Guru's soldiers. In which Bhai Dasa Ji and Bhai Sohela Ji (sons of Ballu Bhat, and grandsons of Mula Bhat) sacrificed their lives.<ref name="bhatra.co.uk">http://www.bhatra.co.uk</ref> | |||

Many Religious Bhats also went to fight as "warrior-saints" against [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] persecution in the [[Khalsa]] campaign inspired by [[Guru Gobind Singh]] Ji. Since many Bhat lived as travelling [[missionary|missionaries]], their mobility led them to depend on occupations which did not require a settled life.<ref name="Sikh Encyclopaedia">[http://www.thesikhencyclopedia.com/main.php?article=199&title=BHATRAS&tgt=B&brief= Sikh Encyclopaedia]</ref> | |||

Bhat Kirat’s grandson Bhat Narbadh (son of Keso Singh) was in attendance to Guru Gobind Singh and accompanied him to Nanded (now Sachkand Hazur Sahib) where Guru Ji spent his last days. In the Bhat-Vahis, Bhat Narbadh records an entry, of the conferment of Guruship upon the Guru Granth Sahib in 1708 upon the death of Guru Gobind Singh.<ref name="bhatra.co.uk"/> | |||

By the 19th century Bhat was the name of a [[Indian caste system|caste]] or ''jati'' within the Indian tradition of social classes, each with its own occupation. Even though Sikhism itself does not support separation by caste, the social system meant that the Bhat followed a hereditary profession of [[missionary|missionaries]], bards,scribes, poets and genealogists while some also foretold the future,<ref>HA Rose, ''Glossary of Tribes and Castes of the Punjab'' (Lahore 1883), quoted by Pradesh</ref> if they were considered to have [[clairvoyant]] or astrological ability's, most of which were from a [[Brahmin]] heritage, eventually becoming salesman due to economic change however it is not uncommon to see Bhats in other professions such as farming and retail. According to Nesfield as quoted in W. Crooke, The Tribes and Castes of the North Western India, 1896, Bhats frequently visited the courts of princes and the camps of warriors, recited their praises in public, and kept records of their genealogies. They have been praised for business acumen, described as people with "a spirit of enterprise".<ref>[http://www.thesikhencyclopedia.com/main.php?article=199&title=BHATRAS&tgt=B&brief= Sikh Encyclopedia]</ref> They were a small clan compared to others and many people in india did not know of them.<ref name="Pradesh">Pradesh</ref> Though some lived in Lahore, many Bhat can trace their roots to villages around Sialkot and Gurdaspur Districts.<ref name="Pradesh"/> | |||

In the 21st century due to the changing world and new opportunities which are available to all people of the world, Bhats have almost completely left their missionary and hereditary professions, to pursue careers in Engineering, Medicine, Law, Banking, Politics, Arts, Hospitality, Sikh Priest hood and much more. | |||

==Heritage of Bhatra Sikhs in the UK== | ==Heritage of Bhatra Sikhs in the UK== | ||

Revision as of 15:35, 18 January 2015

Template:Use British English Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox ethnic group

The Bhat, Bhatt, Bhatta or commonly known as the Bhatra community, refers to a priest, Bard, scribe in Sanskrit, a title given to learned Hindu Brahmins, Sikhs and Muslims with Saraswat Brahmin heritage. This community are also known as the Sangat community and are comprised majorly of Sikh, there is also a size able Muslim community (Bhat clan). Today in the United Kingdom there are significant numbers of Sikhs with Bhat ancestry, as there are in India. The majority Bhat Sikhs originate from Punjab and were among the first followers of Guru Nanak. In the Punjab most Bhat Sikhs are now in Patiala, Amritsar, Nawashahar, Hoshiarpur, Gurdaspur or Bhathinda districts, or in Jalandhar or Chandigarh; elsewhere in India they tend to live in cities, particularly Delhi.

Introduction to the Bhatra Sikhs

The Bhatra/Bhat Sikhs were originally northern hindu Saraswat Brahmins who eventually became Sikhs, these Brahmins were autochthonous inhabitants who helped found the Indus-Saraswati civilization during 4000-2000BC. They lived in the 700+ archeological sites discovered along the former Saraswati River that once flowed parallel to the Indus in present day Kashmir, Himachal, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan regions. As the intellectual and priestly class of that ancient civilization, they are highly respected and honored for creating the world's oldest literary and religious traditions. They were the original propagators (some argue composers too) of the revered texts such as the Vedas and the Upanishads and took these texts into other parts of South Asia. They are considered to be the descendants of the revered Brahmin, Sage Saraswat Muni, who lived on the banks of the ancient river Saraswati.[1] Around 1900 BC, the river Saraswati started vanishing under ground and the people on its banks started migrating to other parts of South Asia thus forming sub-communities. During the Islamic invasions of modern day Pakistan and india, many Saraswat Brahmins were forced to flee due to religious oppression. Such as the saraswat Brahmin Kashmiri Pandit.

Religious Oppression

An estimate of the number of people killed, based on the Muslim chronicles and demographic calculations, was done by K.S. Lal in his book Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India, who claimed that between 1000 CE and 1500 CE, the population of Hindus decreased by 80 million. Sir Jadunath Sarkar contends that that several Muslim invaders were waging a systematic jihad against Hindus in India to the effect that "Every device short of massacre in cold blood was resorted to in order to convert heathen subjects."[2] In particular the records kept by al-Utbi, Mahmud al-Ghazni's secretary, in the Tarikh-i-Yamini document several episodes of bloody military campaigns.[3] In the early 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni launched seventeen expeditions into South Asia. In 1001, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni defeated Raja Jayapala of the Hindu Shahi Dynasty of Gandhara, the Battle of Peshawar and marched further into Peshawar and, in 1005, made it the center for his forces. The Ghaznavid conquests were initially directed against the Ismaili Fatimids of Multan, who were engaged in an on-going struggle with the Abbasid Caliphate in conjunction with their compatriots of the Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa and the Middle East; Mahmud apparently hoped to curry the favor of the Abbasids in this fashion. However, once this aim was accomplished, he moved onto the richness of the loot of wealthy temples and monasteries. By 1027, Mahmud had captured parts of North India and obtained formal recognition of Ghazni's sovereignty from the Abbassid Caliph, al-Qadir Billah.

Ghaznavid rule in Northwestern India lasted over 175 years, from 1010 to 1187. It was during this period that Lahore assumed considerable importance apart from being the second capital, and later the only capital, of the Ghaznavid Empire. At the end of his reign, Mahmud's empire extended from Kurdistan in the west to Samarkand in the Northeast, and from the Caspian Sea to the Punjab. Although his raids carried his forces across Northern and Western India, only Punjab came under his permanent rule; Kashmir, the Doab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat remained under the control of the local Rajput dynasties.

The Sultan's army was easily defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins. Before the battle for Delhi, Timur executed more than 100,000 Hindu captives.[4]

[4][5][6] Timur's purported autobiography, the Tuzk-e-Taimuri ("Memoirs of Temur") is a later fabrication, although most of the historical facts are accurate.[7] As per Malfuzat-i-Timuri,[5] Timur targeted Hindus. In his own words, "Excepting the quarter of the saiyids, the 'ulama and the other Musalmans [sic], the whole city was sacked". In his descriptions of the Loni massacre he wrote, "..Next day I gave orders that the Musalman prisoners should be separated and saved." During the ransacking of Delhi, almost all inhabitants not killed were captured and enslaved.

Timur's memoirs on his invasion of India describe in detail the massacre of Hindus, looting plundering and raping of their women and children, their forced conversions to Islam and the plunder of the wealth of Hindustan (Greater India). It gives details of how villages, towns and entire cities were rid of their Hindu male population through systematic mass slaughters and genocide and their women and children forcefully converted en masse to Islam from Hinduism. Up to about the beginning of the 13th century, Islam became the dominant religion in Kashmir as a large number of Saraswat Kashmiri Pandits were converted to Islam. Mahmud's armies looted temples in Varanasi, Mathura, Ujjain, Maheshwar, Jwalamukhi, Somnath and Dwarka.

The Sayyid (1414–51), and the Lodhi (1451–1526). Muslim Kings extended their domains into Southern India, Kingdom of Vijayanagar resisted until falling to the Deccan Sultanate in 1565. Certain kingdoms remained independent of Delhi such as the larger kingdoms of Punjab, Rajasthan, parts of the Deccan, Gujarat, Malwa (central India), and Bengal, nevertheless all of the area in present-day Pakistan came under the rule of Delhi. The Sultans of Delhi enjoyed cordial, if superficial, relations with Muslim rulers in the Near East but owed them no allegiance. They based their laws on the Quran and the sharia and permitted non-Muslim subjects to practice their religion only if they paid the jizya (poll tax). They ruled from urban centres, while military camps and trading posts provided the nuclei for towns that sprang up in the countryside.

Sikhism

The destruction of Hindu temples in India during the Islamic conquest of India occurred from the beginning of Muslim conquest until the end the Mughal Empire throughout the Indian subcontinent. In the book "Hindu Temples - What Happened to Them", Sita Ram Goel produced a politically contentious list of 2000 mosques that it is claimed were built on Hindu temples.[8] During the 14th to 16th century many Saraswat Brahmins were forced to lead unsettled lifes, unable to practice their hereditary profession as Hindu priests, artists, teachers, scribes, technicians class (varna). They used their academia in there unsettled life travelling as scribes, genealogies, bards and astrologists. In the 15th century the religion of Sikhism was born causing many to follow the word of Guru Nanak Dev Ji. Further conversions of the Saraswat Brahmins Bhats to Sikhism were induced by a royal preacher by the name of Prince Baba Changa Bhat Rai.

Bhat/Bhatra tradition and Sikh text states their ancestors came from Punjab, where the Raja Shivnabh and his kingdom became the original 16th century followers of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. The Raja's grandson Prince Baba Changa after studying and competing in competition for 14 years under the high Pandit Chetan Gir earned the title ‘Bhat Rai’ – the ‘Raja of Poets, and then settled himself and his followers all over India as missionaries to spread the word of Guru Nanak, where most of northern Saraswat Brahmin Bhat became Bhat Sikhs. The Bhats also contributed 123 compositions in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib (pp.1389–1409), known as the "Bhata de Savaiyye".[9] They also wrote the Bhat Vahis, which were scrolls or records on the Gurus and Sikhism maintained by the Bhat Sikhs. As Guru Nanak and Sikhism do not support the caste system, the Bhat people do not consider themselves as a caste in the typical sense due to the message of Guru Nanak, but a clan within Sikhism linked by Guru Nanak which is not shackled by the caste system. The majority were from the northern Saraswat Brahmin caste (Bhat clan),(Bhat (surname)) as the Prince Baba Changa Bhat Rai although a kshatriya, trained under Brahmins scholars and shared the Bhat Brahmin heritage due to his passion for religion, many continued to be called the Bhat/Bhat-rai sikhs, eventually leading to the name Bhat-ra Sikh. The sangat also had many members from different areas of the Sikh caste spectrum, such as the Hindu Rajputs and Hindu Jats who joined due to Bhat sikh missionary efforts. The Ramaiya community of Uttar Pradesh is said to be a sub-clan of Bhatra origin.[10] Currently there are many Hindus and Muslims that share the Brahmin Bhat heritage.[11] Today modern Bhat sikhs are commonly known to have pioneered many of the first Gurdwaras outside of India and have donated to various Gurdwaras.

In the 17th century Bhats Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das were Saraswat Mohyal Brahmin[12][13] and were disciples of the ninth Sikh Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675). They were executed along with the Guru at the Kotwali (police-station) near the Sunehri Masjid in the Chandni Chowk area of Old Delhi, under the express orders of emperor Aurangzeb. Bhat Bhai Sati Das was wrapped in cotton wool and set on fire by the Mughal authorities for refusing to denounce his faith. His brother Bhat Bhai Mati Das was also tortured to death, by having his head sawn in two.

On 16 December 1634 the Sikh forces under the command of Rai Jodh and Kirt Bhat waged a guerrilla attack on Mughal forces at night, whereby the Sikhs routed and defeated the enemy. Guru Sahib lost 1200 Saint Soldiers including Kirat Bhat Ji. On the other side Sameer Beg and his two sons Shams Beg and Qasim Beg were also killed. The Mughal forces fled to Lahore leaving behind the dead and wounded.

After the Battle of Kartarpur, Guru Hargobind Sahib moved towards Kiratpur Sahib, which was under the rule of Raja Tara Chand (a hill state chief). Guru Sahib's entourage was suddenly ambushed by a contingent of royal forces under the command of Ahmed Khan in the village Palahi near Phagwara town on 29 April 1635. It caused considerable loss on the Guru's soldiers. In which Bhai Dasa Ji and Bhai Sohela Ji (sons of Ballu Bhat, and grandsons of Mula Bhat) sacrificed their lives.[14]

Many Religious Bhats also went to fight as "warrior-saints" against Mughal persecution in the Khalsa campaign inspired by Guru Gobind Singh Ji. Since many Bhat lived as travelling missionaries, their mobility led them to depend on occupations which did not require a settled life.[15]

Bhat Kirat’s grandson Bhat Narbadh (son of Keso Singh) was in attendance to Guru Gobind Singh and accompanied him to Nanded (now Sachkand Hazur Sahib) where Guru Ji spent his last days. In the Bhat-Vahis, Bhat Narbadh records an entry, of the conferment of Guruship upon the Guru Granth Sahib in 1708 upon the death of Guru Gobind Singh.[14]

By the 19th century Bhat was the name of a caste or jati within the Indian tradition of social classes, each with its own occupation. Even though Sikhism itself does not support separation by caste, the social system meant that the Bhat followed a hereditary profession of missionaries, bards,scribes, poets and genealogists while some also foretold the future,[16] if they were considered to have clairvoyant or astrological ability's, most of which were from a Brahmin heritage, eventually becoming salesman due to economic change however it is not uncommon to see Bhats in other professions such as farming and retail. According to Nesfield as quoted in W. Crooke, The Tribes and Castes of the North Western India, 1896, Bhats frequently visited the courts of princes and the camps of warriors, recited their praises in public, and kept records of their genealogies. They have been praised for business acumen, described as people with "a spirit of enterprise".[17] They were a small clan compared to others and many people in india did not know of them.[18] Though some lived in Lahore, many Bhat can trace their roots to villages around Sialkot and Gurdaspur Districts.[18]

In the 21st century due to the changing world and new opportunities which are available to all people of the world, Bhats have almost completely left their missionary and hereditary professions, to pursue careers in Engineering, Medicine, Law, Banking, Politics, Arts, Hospitality, Sikh Priest hood and much more.

Heritage of Bhatra Sikhs in the UK

Bhatra Sikhs started to arrive in the United Kingdom in the 1920s, but most immigrated in the late 1940s or 1950s..

Bhatra tradition and traditional Sikh literature say their ancestors came from Punjab, were the original 16th century followers of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. In the 17th century some religious Bhatra went to fight as "warrior-saints" against Mughal persecution in the Khalsa campaign inspired by Guru Gobind Singh Ji. Since many Bhatra lived as travelling missionaries, their mobility led them to depend on occupations which did not require a settled life.[19]

By the 19th century Bhatra was the name of a caste or jati within the Indian tradition of social classes, each with its own occupation. Even though Sikhism itself does not support separation by caste, the social system meant that the Bhatra followed a hereditary profession of itinerant salesman, while some also foretold the future,[20] if they were considered to have clairvoyant ability. They have been praised for business acumen, described as people with “a spirit of enterprise”.[21] They were a small group: so small that even in the Punjab many people did not know of them.[22] Though some lived in Lahore, many Bhatra can trace their roots to villages around Sialkot and Gurdaspur Districts.[23]

In the 1920s some men travelled to Britain to work as door-to-door salesmen, most leaving their families in the Punjab to begin with. By the time of the Second World War there were a few hundred Sikhs clustered in British seaports like Cardiff, Bristol, and Southampton. Some returned to India when war broke out, but others stayed on and used contacts with Punjabi merchant seamen to import scarce goods.

Partition

The Partition of India in 1947 led many Sikhs to emigrate, and the Bhatra population in the UK was greatly enlarged. Later arrivals tended to join relatives, friends and neighbours from the Punjab, so that some British Bhatra communities have links to one or two particular villages.[24] Difficult journeys following Partition are not forgotten. The Edinburgh Sikh women's group (Sikh Sanjog) has exhibited artwork telling the story of leaving the Punjab and arriving in a strange land.

A 2001 obituary of a senior figure in the Cardiff Bhatra community described the trials of leaving northern India in turbulent times.[25]

Jobs

The traditional Bhatra profession of itinerant salesman was useful to those arriving in the UK, and was "a skill with considerable potential".[26] At first most Bhatra, like some other Sikhs, worked either as doorstep or market traders (working with the Khatri community), but some settled in big cities like Leeds or Birmingham, gave up self-employment and took waged jobs in industry. (At this time many educated immigrants to Britain had difficulty finding employment suited to their qualifications and experience, because of racial and/or cultural prejudice.)

Bhatra traders gradually moved into other roles as self-employed businessmen, often specialising in retailing. By the end of the 1950s selling door-to-door was less common and many British Bhatra Sikhs moved towards commercial enterprises like market stalls, shops, supermarkets and wholesale warehouses.[27] Nowadays the younger Bhatra genaration are represented in many varied professions from doctors to accountants, from engineers to musicians.

Gurdwaras

When possible the Bhatra community has established its own Gurdwaras (temples), the first of which was opened in Manchester in 1953.[28] As of 2006 there are more than 30 Bhatra or Bhat Sikh temples in the UK, the newest being the one opened in Peterborough in 2004. In some British towns Bhatras are a small proportion of the overall Sikh population (in Glasgow 5%); elsewhere, as in Edinburgh, they are in the majority. .[29]

The London Bhatra Comunity

The Bhatra Gurdwaras in the UK are someimes linked with ongoing community projects. The site of the first Sangat Bhatra Gurdwara in London, in Mile End Bow in Campbell Road, is still in service and of interest to social historians. The Community also moved to a retired Synagogue in a Grade Two listed building in Harley Grove, East London, recognised as a fine example of Jewish Architecture. This fits with Sikh beliefs in tolerance and respect for other cultures. The Harley Grove Gurdwara has large Vasakhi celebrations at the Sikh New Year, and is a focal point for Bhatra Sikhs in London. This Community is led by Trustee Gurupashad Bance, a respected community figure currently sitting on the UK National Governing Sikh Council, who has pioneered active Sikh and civic engagement.

The Scotland Bhatra Communiy

In 1964 The first Gurdwara in Endinburgh was established at 7 Hope Terrace,Leith,Edinburgh. The House belonged to two brothers Gholu singh Roudh and Mangal Singh Roudh, who kindly donated the property to be used as a Gurdwara by the Sikh Community. Furthermore the above were the first sikh settlers in Edinburgh. Also check the link at Bhatra.co.uk on Edinburgh Sikhs. Roudh

Origins

Many Bhatras consider themselves a sangat (fellowship) which originated with Guru Nanak's visit to Sri Lanka. The Sikh Encyclopedia says that "more than one story is current about their origin". One tradition says Bhatra people are descended from Changa Rai or Changa Bhatra, a disciple of Guru Nanak's mentioned in the Janamsakhis. A congregation led by a teacher called Baba Changa Rai is described in an old document called the Haqiqat Rah Muqam.[30]

Sri Lanka

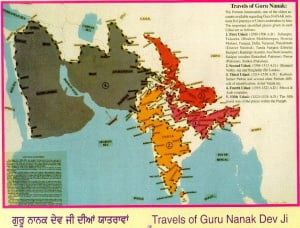

M.S. Ahluwalia, a Senior Fellow at the Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi, offers historical evidence for Guru Nanak's presence in Sri Lanka, probably in the year 1510.[31] Many scholars, though not all, agree that the Guru visited Sri Lanka on his travels.

Baba Changa Rai

According to the Sikh Encyclopedia, Bhatra is related to the Sanskrit word bhatta, or bhat, a bard or poet. Although the encyclopedia points out that there is more than one explanation of Bhatra origins, they discuss a link between Bhatra Sikhs and Changa Bhatra, also known as Baba Changa Rai, or Changa Bhai, of Sri Lanka, who became a disciple of Guru Nanak Dev Ji. He added Bhatra to his name and spread the word of Guru Nanak to his followers, who also became known as Bhatra.[32] The meeting of Guru Nanak and Changa Bhatra is said to have taken place about 12 miles south of his meeting with the Raja.[33]

Challenge to tradition

A place called Singaldeep or Sangladeep is often mentioned in traditional histories of Rja shiv Nabh and is usually understood to be in sri lanka. Bhatra history may also mention connections with the Raja Shiv Nabh [citation needed], ruler of Batticaloa and an early disciple of Guru Nanak.[34]

Bhatra Sangat name groups

First of all there are two main groups: Darewal and the Landervaser. The Landervaser are from a village farming background.

There is a story that the Names of the Jart came from certain tribal groups with names representing animals like dragons, lions, tigers and elephants. The names are as follows:

|

and many more........ |

These help to stop the families getting married to their own relatives. It is not acceptable to marry someone who has the same father's family name.

Culture

Commentators have found Bhatra Sikhs pride themselves on an orthodox approach to their religion, and many have more conservative attitudes than other Sikhs.[35]Though Sikhism supports equality for women, a generation ago researchers found some Bhatra girls were withdrawn from English schools before the official leaving age of 16, and their fathers said they wanted to "prepare them for marriage, e.g. train them in cooking, housekeeping, embroidery and sewing".[36] While this may no longer be the case, some still feel that girls should be preparing for marriage and motherhood.[37]

Food

Sharing food or Langar is important in Sikhism, and each Gurdwara has a community centre with its own kitchen.

Drink

When boys are born in Bhatra communities it is customary to open a bottle of whisky or other fine drink, to celebrate the birth of the baby boy.

Marriage

Marriages arranged by the couple's parents are common. Sikh Bhatra believe that by arranging their son's or daughter's marriage they will be able to ensure that their son/daughter will be matched up with the right partner, the right family and hopefully have a stable and happy future. Another reason for doing this, for Bhatra and many other communities, is to keep tradition, culture and religion alive. In most cases parents will accompany the son/daughter when finding their partner as the parents usually help in finding a suitable match.[38] In 1999 arranged marriages were found to be almost the rule in some UK Bhatra communities (for instance, Edinburgh) while elsewhere about half of Bhatra Sikh marriages are arranged by the parents (for instance, Birmingham).[39] This is similar to the frequency of arranged marriage in other UK Asian communities.[40]

The typical age of marriage in the Bhatra community is younger than in the UK as a whole, although there are signs of change as more go into higher education or focus on careers.[citation needed] Most Sikh marriages in the UK involve members of the same caste.[41][42] Wedding ceremonies in their various stages may last up to two weeks or more. The BBC filmed a Bhatra wedding in 1997 which was a "blind marriage" involving a bride and groom who had not seen each other before the ceremony.[43]These are becoming rare and involve only a small minority of Sikhs.

Some wedding ceremonies take 3 days and involve close relatives staying at the groom's family home.

Names for relationships within the family

- Bupu - Papa: Father, Grandfather

- Bebe - Bube: Mother, Grandmother

- Chacha - Chuche: Younger than Father

- Thi-ya - Theuy: Older than Father

- Pupore: Uncle To Sister

- Prajai: Brother's Wife

Early experiences of the UK

A poem written by the late Sardar Singh Sathi (Suwali), who was a well known member of the Bhatra Sikh sangat, describes their early days in the UK. This is an extract from the beginning of the poem.[citation needed]

jamday nu gurti pairo dee

bebay te lala ladin deh

tak hoya satta sala da

lala hee karo parah-din deh

phir lakay course lafti da

te begah haath pira-din deh

kenday ne puttar katu hai

jadh pounda do kama-din deh

ki lenay evay par-likh kay

jadh parnay beghay akar nay

lala te mala donay hee

phir peenday johnny walker nay.

Further information

See also: List of Sikhism-related topics

Prince Charles has a long-term interest in Sikhism and has met Bhatra Sikhs in various parts of the UK, praising their community work in Manchester.

Other Sikhs in the UK

Although Sikhism does not support the old Indian caste system, in the UK there are some tensions between Jat Sikhs and Bhatra Sikhs which probably have an element of leftover caste prejudice.[44] Jat Sikhs are the biggest group of the approximately 600,000 Sikhs in the UK, though in the first half of the 20th century they and the Bhatra Sikhs had equal numbers of people in the country. The Jats worked as "door-knock" salesmen then too, though it was not their traditional occupation (farming).[45] Ramgharia Sikhs (traditionally wood workers and craftsmen)[46] are another sizeable group.

Films and music

See also: Music of Punjab

Actors, films, music and musicians which may be of special interest to Sikhs in the UK include:

- Baleah Baleh - a traditional Punjabi folk-singer

- Gandhi - the film directed by Richard Attenborough which portrays the Amritsar massacre

- Films with Gurdas Maan

- Dholki drumming - a traditional art

- Jasbir Singh Bhogal, tabla player

- Rhythm Dohl Bass (RDB), a Bhangra group

- Mehsopuria, a Bhangra singer

- Sukhi Roudh UK Bhangra singer with DJ Kendal

- Gurdas Singh Roudh Bhangra Singer aka G-ROTH

Historical figures

See also: List of prominent Sikhs

People of historical importance for Sikhs in the UK include:

Bibliography

- Desh Pradesh, Differentiation and Disjunction among the Sikhs in South Asian Experience in Britain (1994) ed. Roger Ballard

- Roger Ballard, The Growth and Changing Character of the Sikh Presence in Britain in The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States (2000), ed. Harold Coward, Raymond Brady Williams, John R Hinnells

- Roger Ballard, Migration,Remittances, Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction: Reflections on the basis of South Asian Experience

- R and C Ballard, The Sikhs: the development of South Asian settlements in Britain in Between Two Cultures ed. JL Watson (1977)

- P Ghuman, Bhattra Sikhs in Cardiff: Family and Kinship Organization. New Community (1980) 8, 3.

- Marie Gillespie, Television, Ethnicity and Cultural Change (Routledge 1995)

- Malory Nye, A Place for Our Gods: The Construction of an Edinburgh Hindu Temple Community (1995)

- Eleanor Nesbitt, Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction (OUP 2005) ISBN 0-19-280601-7

- Difference within Sikh Communities

- Sikh settlers in Britain (includes material on caste and on "Bhattra")

- The Sikh Encyclopedia

References

- ^ {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [[{{{authorlink}}}|{{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | {{{author}}} }}]] | {{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | {{{author}}} }} }} }}{{ #if: | {{ #if: | ; {{{coauthors}}} }} }}{{ #if: | [{{{origdate}}}] | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [{{{origmonth}}} {{{origyear}}}] | [{{{origyear}}}] }} }} }}{{ #if: | ({{{date}}}) | {{ #if: 2008 | {{ #if: | ({{{month}}} 2008) | (2008) }} }} }}{{ #if: | . }}{{ #if: | "{{ #if: | [{{{chapterurl}}} {{{chapter}}}] | {{{chapter}}} }}",}}{{ #if: | in {{{editor}}}: }} {{ #if: http://books.google.co.th/books?id=VMM-xRVr5qgC&pg=PA35&lpg=PA35&dq=kashmiri+pandits+saraswat+brahmins&source=bl&ots=2DzIpkFhQn&sig=l2muBsQVSQgeQyC3zJILTwDWdLw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=aAH3T5bTMo3rrQe20IHUBg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=kashmiri%20pandits%20saraswat%20brahmins&f=false | Kashmiri Pandits: Looking to the future | Kashmiri Pandits: Looking to the future }}{{ #if: | ({{{format}}}) }}{{ #if: | , {{{others}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{edition}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{series}}} }}{{ #if: | (in {{{language}}}) }}{{ #if: APH Publishing House | {{#if: | , | . }}{{ #if: 5, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi | 5, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi: }}APH Publishing House }}{{ #if: 32 | , 32 }}{{ #if: | . DOI:{{{doi}}} }}{{ #if: | . {{{id}}} }}{{ #if: 8176482366 | . ISBN 8176482366 }}{{ #if: | . OCLC {{{oclc}}} }}{{ #if: http://books.google.co.th/books?id=VMM-xRVr5qgC&pg=PA35&lpg=PA35&dq=kashmiri+pandits+saraswat+brahmins&source=bl&ots=2DzIpkFhQn&sig=l2muBsQVSQgeQyC3zJILTwDWdLw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=aAH3T5bTMo3rrQe20IHUBg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=kashmiri%20pandits%20saraswat%20brahmins&f=false | {{ #if: 7 July 2012 | . Retrieved on 7 July 2012 | {{ #if: | . Retrieved {{ #if: | on [[{{{accessmonth}}} {{{accessyear}}}]] | during [[{{{accessyear}}}]] }}}} }} }}.{{ #if: | “{{{quote}}}” }} </in

- ^ {{ #if: Sarkar | {{ #if: Jadunath Sarkar | {{ #if: Sarkar | Sarkar{{ #if: Jadunath | , Jadunath }} | {{{author}}} }} | {{ #if: Sarkar | Sarkar{{ #if: Jadunath | , Jadunath }} | {{{author}}} }} }} }}{{ #if: Sarkar | {{ #if: | ; {{{coauthors}}} }} }}{{ #if: | [{{{origdate}}}] | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [{{{origmonth}}} {{{origyear}}}] | [{{{origyear}}}] }} }} }}{{ #if: | ({{{date}}}) | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | ({{{month}}} {{{year}}}) | ({{{year}}}) }} }} }}{{ #if: Sarkar | . }}{{ #if: | "{{ #if: | [{{{chapterurl}}} {{{chapter}}}] | {{{chapter}}} }}",}}{{ #if: | in {{{editor}}}: }} {{ #if: | [{{{url}}} How the Muslims forcibly converted the Hindus of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to Islam] | How the Muslims forcibly converted the Hindus of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to Islam }}{{ #if: | ({{{format}}}) }}{{ #if: | , {{{others}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{edition}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{series}}} }}{{ #if: | (in {{{language}}}) }}{{ #if: | {{#if: | , | . }}{{ #if: | {{{location}}}: }}{{{publisher}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{page}}} }}{{ #if: | . DOI:{{{doi}}} }}{{ #if: | . {{{id}}} }}{{ #if: | . ISBN {{{isbn}}} }}{{ #if: | . OCLC {{{oclc}}} }}{{ #if: | {{ #if: | . Retrieved on [[{{{accessdate}}}]] | {{ #if: | . Retrieved {{ #if: | on [[{{{accessmonth}}} {{{accessyear}}}]] | during [[{{{accessyear}}}]] }}}} }} }}.{{ #if: | “{{{quote}}}” }} </in

- ^ {{ #if: Sir H. M. Elliot | {{ #if: | [[{{{authorlink}}}|{{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | Sir H. M. Elliot }}]] | {{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | Sir H. M. Elliot }} }} }}{{ #if: Sir H. M. Elliot | {{ #if: | ; {{{coauthors}}} }} }}{{ #if: | [{{{origdate}}}] | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [{{{origmonth}}} {{{origyear}}}] | [{{{origyear}}}] }} }} }}{{ #if: | ({{{date}}}) | {{ #if: 1869 | {{ #if: | ({{{month}}} 1869) | (1869) }} }} }}{{ #if: Sir H. M. Elliot | . }}{{ #if: Chapter II, Tarikh Yamini or Kitabu-l Yamini by Al Utbi | "{{ #if: | [{{{chapterurl}}} Chapter II, Tarikh Yamini or Kitabu-l Yamini by Al Utbi] | Chapter II, Tarikh Yamini or Kitabu-l Yamini by Al Utbi }}",}}{{ #if: | in {{{editor}}}: }} {{ #if: http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924073036729#page/n39/mode/2up | The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period | The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period }}{{ #if: | ({{{format}}}) }}{{ #if: | , {{{others}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{edition}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{series}}} }}{{ #if: | (in {{{language}}}) }}{{ #if: Trubner and Co | {{#if: | , | . }}{{ #if: | {{{location}}}: }}Trubner and Co }}{{ #if: 14–52 | , 14–52 }}{{ #if: | . DOI:{{{doi}}} }}{{ #if: | . {{{id}}} }}{{ #if: | . ISBN {{{isbn}}} }}{{ #if: | . OCLC {{{oclc}}} }}{{ #if: http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924073036729#page/n39/mode/2up | {{ #if: | . Retrieved on [[{{{accessdate}}}]] | {{ #if: | . Retrieved {{ #if: | on [[{{{accessmonth}}} {{{accessyear}}}]] | during [[{{{accessyear}}}]] }}}} }} }}.{{ #if: | “{{{quote}}}” }} </in

- ^ a b Cahen, Cl.; İnalcık, Halil; Hardy, P. "Ḏj̲izzya." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 29 April 2008

- ^ a b Volume III: To the Year A.D. 1398, Chapter: XVIII. Malfúzát-i Tímúrí, or Túzak-i Tímúrí: The Autobiography or Memoirs of Emperor Tímúr (Taimur the lame). Page: 389 (1. Online copy, 2. Online copy) from: Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; London Trubner Company 1867–1877.)

- ^ {{ #if: Lane-Poole | {{ #if: | [[{{{authorlink}}}|{{ #if: Lane-Poole | Lane-Poole{{ #if: Stanley | , Stanley }} | {{{author}}} }}]] | {{ #if: Lane-Poole | Lane-Poole{{ #if: Stanley | , Stanley }} | {{{author}}} }} }} }}{{ #if: Lane-Poole | {{ #if: | ; {{{coauthors}}} }} }}{{ #if: | [{{{origdate}}}] | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [{{{origmonth}}} {{{origyear}}}] | [{{{origyear}}}] }} }} }}{{ #if: | ({{{date}}}) | {{ #if: 1907 | {{ #if: | ({{{month}}} 1907) | (1907) }} }} }}{{ #if: Lane-Poole | . }}{{ #if: Chapter IX: Tinur's Account of His Invasion | "{{ #if: | [{{{chapterurl}}} Chapter IX: Tinur's Account of His Invasion] | Chapter IX: Tinur's Account of His Invasion }}",}}{{ #if: | in {{{editor}}}: }} {{ #if: | [{{{url}}} History of India] | History of India }}{{ #if: | ({{{format}}}) }}{{ #if: | , {{{others}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{edition}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{series}}} }}{{ #if: | (in {{{language}}}) }}{{ #if: The Grolier Society | {{#if: | , | . }}{{ #if: | {{{location}}}: }}The Grolier Society }}{{ #if: | , {{{page}}} }}{{ #if: | . DOI:{{{doi}}} }}{{ #if: | . {{{id}}} }}{{ #if: | . ISBN {{{isbn}}} }}{{ #if: | . OCLC {{{oclc}}} }}{{ #if: | {{ #if: | . Retrieved on [[{{{accessdate}}}]] | {{ #if: | . Retrieved {{ #if: | on [[{{{accessmonth}}} {{{accessyear}}}]] | during [[{{{accessyear}}}]] }}}} }} }}.{{ #if: | “{{{quote}}}” }} </in Template:Google books

- ^ B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ^ [1] Hindu temples- What happened to them

- ^ [2]

- ^ Sikh Encyclopedia

- ^ [^ http://books.google.com.pk/books?id=QpjKpK7ywPIC&pg=PA365&lpg=PA365&dq=History+of+kashmir+and+its+people&source=bl&ots=-RI_8tLrab&sig=8d9tzPeeB5lAjaq9RZqzYO8QydA&hl=en&ei=ab9pSobcB46PkAXutZW4Cw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6]

- ^ {{ #if: O. P. Ralhan | {{ #if: | [[{{{authorlink}}}|{{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | O. P. Ralhan }}]] | {{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | O. P. Ralhan }} }} }}{{ #if: O. P. Ralhan | {{ #if: | ; {{{coauthors}}} }} }}{{ #if: | [{{{origdate}}}] | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [{{{origmonth}}} {{{origyear}}}] | [{{{origyear}}}] }} }} }}{{ #if: | ({{{date}}}) | {{ #if: 1997 | {{ #if: | ({{{month}}} 1997) | (1997) }} }} }}{{ #if: O. P. Ralhan | . }}{{ #if: | "{{ #if: | [{{{chapterurl}}} {{{chapter}}}] | {{{chapter}}} }}",}}{{ #if: | in {{{editor}}}: }} {{ #if: | [{{{url}}} The Great Gurus of the Sikhs] | The Great Gurus of the Sikhs }}{{ #if: | ({{{format}}}) }}{{ #if: | , {{{others}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{edition}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{series}}} }}{{ #if: | (in {{{language}}}) }}{{ #if: Anmol Publications | {{#if: | , | . }}{{ #if: | {{{location}}}: }}Anmol Publications }}{{ #if: 16 | , 16 }}{{ #if: | . DOI:{{{doi}}} }}{{ #if: | . {{{id}}} }}{{ #if: 978-81-7488-479-4 | . ISBN 978-81-7488-479-4 }}{{ #if: | . OCLC {{{oclc}}} }}{{ #if: | {{ #if: | . Retrieved on [[{{{accessdate}}}]] | {{ #if: | . Retrieved {{ #if: | on [[{{{accessmonth}}} {{{accessyear}}}]] | during [[{{{accessyear}}}]] }}}} }} }}.{{ #if: His life-long companion Bhai Mati Das, a Mohyal Brahmin of village Karyala in Jehlam district... | “His life-long companion Bhai Mati Das, a Mohyal Brahmin of village Karyala in Jehlam district...” }} </in

- ^ {{ #if: Hari Ram Gupta - Sikhs | {{ #if: | [[{{{authorlink}}}|{{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | Hari Ram Gupta - Sikhs }}]] | {{ #if: | {{{last}}}{{ #if: | , {{{first}}} }} | Hari Ram Gupta - Sikhs }} }} }}{{ #if: Hari Ram Gupta - Sikhs | {{ #if: | ; {{{coauthors}}} }} }}{{ #if: | [{{{origdate}}}] | {{ #if: | {{ #if: | [{{{origmonth}}} {{{origyear}}}] | [{{{origyear}}}] }} }} }}{{ #if: | ({{{date}}}) | {{ #if: 1978 | {{ #if: | ({{{month}}} 1978) | (1978) }} }} }}{{ #if: Hari Ram Gupta - Sikhs | . }}{{ #if: | "{{ #if: | [{{{chapterurl}}} {{{chapter}}}] | {{{chapter}}} }}",}}{{ #if: | in {{{editor}}}: }} {{ #if: | [{{{url}}} History of the Sikhs] | History of the Sikhs }}{{ #if: | ({{{format}}}) }}{{ #if: | , {{{others}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{edition}}} }}{{ #if: | , {{{series}}} }}{{ #if: | (in {{{language}}}) }}{{ #if: Munshiram Manoharlal | {{#if: | , | . }}{{ #if: | {{{location}}}: }}Munshiram Manoharlal }}{{ #if: 211 | , 211 }}{{ #if: | . DOI:{{{doi}}} }}{{ #if: | . {{{id}}} }}{{ #if: | . ISBN {{{isbn}}} }}{{ #if: | . OCLC {{{oclc}}} }}{{ #if: | {{ #if: | . Retrieved on [[{{{accessdate}}}]] | {{ #if: | . Retrieved {{ #if: | on [[{{{accessmonth}}} {{{accessyear}}}]] | during [[{{{accessyear}}}]] }}}} }} }}.{{ #if: The Guru's companions included Mati Das, a Mohyal Brahmin... | “The Guru's companions included Mati Das, a Mohyal Brahmin...” }} </in

- ^ a b http://www.bhatra.co.uk

- ^ Sikh Encyclopaedia

- ^ HA Rose, Glossary of Tribes and Castes of the Punjab (Lahore 1883), quoted by Pradesh

- ^ Sikh Encyclopedia

- ^ a b Pradesh

- ^ Sikh Encyclopaedia

- ^ HA Rose, Glossary of Tribes and Castes of the Punjab (Lahore 1883), quoted by Pradesh

- ^ Sikh Encyclopaedia

- ^ Pradesh

- ^ Pradesh

- ^ Nye

- ^ Western Mail, December 13 2001

- ^ Pradesh

- ^ Pradesh

- ^ Sikh Encyclopaedia

- ^ Glasgow Herald, April 17 1999

- ^ Haqiqat Rah Muqam "included in Bhai Banno's "bir", according to the Sikh Encyclopedia and others.

- ^ M.S. Ahluwalia, Guru Nanak in Ceylon (Sikh Spectrum Quarterly 2004)

- ^ Sikh Encyclopaedia

- ^ Kirpal Singh, Janamsakhi Tradition (Amritsar 2004)

- ^ For more on Guru Nanak's journey to Batticaloa/Batticola see: Kirpal Singh, Janamsakhi Tradition (Amritsar 2004)

- ^ Pradesh, also Ghuman

- ^ Study by Thomas and Ghuman (1980) quoted by Paul A Singh Ghuman in South Asian Girls in Secondary schools: A British Perspective

- ^ Sikh Sanjog: the Family

- ^ Sikh marriage traditions

- ^ Glasgow Herald, April 17 1999

- ^ Roger Penn and Peter Lambert, Arranged Marriages in Western Europe 2002

- ^ Gillespie

- ^ Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought (2003)

- ^ Daily Record, February 17 1997

- ^ Nye, also Glasgow Herald, April 17 1999, and others

- ^ William Gould, Hindu Nationalism and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial India: Glossary

- ^ Gillespie

External links

- Bhatra in the UK before Partition

- Sikh Sanjog

- Sikh Directory UK - includes Bhatra Gurdwaras

- Cardiff Bhatra Gurdwara

- Bhat Sikh Community in Peterborough

| Sects & Cults |

|

♣♣ Ad Dharm ♣♣ Akalis ♣♣ Bandai Sikhs ♣♣ Balmiki ♣♣ Bhatra ♣♣ Brindaban Matt ♣♣ Daya Singh Samparda ♣♣ Dhir Malias ♣♣ Handalis ♣♣ Kabir Panthi ♣♣ Kirtan jatha Group ♣♣ Kooka ♣♣ Kutta Marg ♣♣ Majhabi ♣♣ Manjis ♣♣ Masand ♣♣ Merhbanieh ♣♣ Mihan Sahibs ♣♣ Minas ♣♣ Nirankari ♣♣ Nanak panthi ♣♣ Nanakpanthi Sindhis ♣♣ Namdev Panthi ♣♣ Namdhari ♣♣ Nanaksaria ♣♣ Nihang ♣♣ Nikalsaini ♣♣ Niranjaniye ♣♣ Nirmala ♣♣ Panch Khalsa Diwan ♣♣ Parsadi Sikhs ♣♣ Phul Sahib dhuan ♣♣ Radha Swami ♣♣ Ram Raiyas ♣♣ Ravidasi ♣♣ Ridváni Sikhs ♣♣ Suthra Shahi ♣♣ Sewapanthi ♣♣ Sat kartaria ♣♣ Sant Nirankaris ♣♣ Sanwal Shahis ♣♣ Sanatan Singh Sabhais ♣♣ Sachkhand Nanak Dhaam ♣♣ Samparda Bhindra ♣♣ Tat Khalsa ♣♣ Sikligars ♣♣ Pachhada Jats ♣♣ Satnami's ♣♣ Udasi Sikhs ♣♣ |