Guru ki maseet

Guru ki Maseet or Guru's Mosque is a mosque that was constructed at the request of the sixth Sikh Guru Guru Hargobind ji. It is situated in Sri Hargobindpur town on the banks of River Beas. It is also recognized as a historic site by UNESCO.

When Hargobind Sahib ji was anointed the sixth guru of the Sikhs he asked Baba Buddha ji, an eminent Sikh to bring forth two swords. These Guru Sahib put on as symbols of spiritual (miri) and temporal (piri) authority. Guru Hargobind Sahib is known as ‘miri piri thay malik’, "Lord of miri and piri".

Guru Hargobind sahib built the Akal Takhat Sikhi's most important Temporal throne, the throne of the Almighty, opposite the Harimandar Sahib (Golden temple), Sikhi's most revered spiritual Gurdwara, again this was an additional sign of bringing together spiritual and temporal powers.

In December, 1634 Guru Hargobind Sahib fought a fierce battle against Mughal forces near the River Beas. Although heavily outnumbered, the Guru was victorious. Guru Sahib decided to stay there for a while, and soon a settlement grew up at this location. The settlement expanded into a town which became known as Sri Hargobindpur (-pur, being a suffix for "place of").

As the conflict with the Mughals was intensifying the town's defences were fortified. In fact, these fortifications were so solid that the original city walls and many buildings within are still visible today throughout Sri Hargobindpur in Gurdaspur district, Punjab.

Residents of all faiths flocked to the Guru and perceived themselves as heirs to the sixth Guru’s desire to found a secure and secular home on the banks of the Beas. The Sikhs built themselves a Gurdwara (Sikh temple) but the local Muslims did not have the capacity to build themselves a place of worship due to their smaller numbers. They came to the Guru and asked him for help.

The wise Guru was as respectful of Muslim faqirs as he was with Hindu sadhus and his Sikh followers; he viewed people of the differing religions of India with one benevolent gaze. The Guru ordered his Sikhs to start construction of a "Masjid" (mosque). The Masjid was duly completed and duly handed over to the Muslims.

This mosque has existed in this location since the period of the sixth Guru. With the turmoil of the partitioning of India in 1947 and the mass movement of people, the mosque fell into a state of neglect and disrepair. In time the care of the Masjid fell into the hands of a group a Nihang Singhs who installed the Sikh scripture Shri Guru Granth Sahib in the one-time Masjid. For many years, the mosque was maintained by these Nihangs.

In February 8th, 2003 a “Memorandum of Understanding” (MoU) was signed by Baba Kirtan Singh the chief of the Nihangs, the Sikh caretakers of the mosque, and the Punjab Waqf Board. It was Baba Kirtan Singh's desire that Muslims again perform their prayers at the mosque which had been gifted to them by Guru Hargobind.

As per the wishes of Baba Kirtan Singh, five saplings were planted in the names of five Sikh Gurus. Dr Mohammad Rizwanul Haque, Punjab Waqf Board Administrator, described the MoU as an international event which would pave the way for strengthening communal harmony in the country.

The mosque was in a state of disrepair and work was begun on its restoration by a group of Sikhs and Muslims in a unique manifestation of India's multi-religious society, at least as the Sikhs have often practised it and as the Muslim masons joined in as well.

Kar Sewa (hard labour - freely given)

Sikhs offered their labour while the Muslim masons repaired the walls and an all-woman team of restorers led by Ms Gurmeet Kaur Rai lent its restoration expertise. The people of the entire village, and even those from the surrounding areas, answered Rai's call for clearing the earth around the shrine. Hundreds of school children and Nihangs did the spadework.

Today the mosque has been excavated as the years had seen the ground around the site rise. "We will now try and remove all later additions, like cement, plaster and white-wash from the brick structure, and then apply lime paste plaster, which will allow the building to breathe," said Rai. The work was finally completed on March 23rd, 2004.

The performance of Muslim religious prayers in the mosque after 55 years would be recorded in history as an event when Sikhs showed so much magnanimity towards Muslims, said Dr Mohammed Rizwanul Haque.

In a similar event a year ago Sikhs of Chahar Mazra village in Ropar District built a mosque for their Muslim neighbours. Sant Varyam Singh, who heads Vishwa Gurumat spiritual mission in the adjacent Ratwara Sahib village, built the mosque for the Muslims of the area. The first prayers were offered in March last year. After the prayers there were heart-warning scenes of celebrations and Muslims embracing their Sikh brethren.

The Guru’s civic plan reflected this understanding of the concept of God having multiple names but being one entity as the town includes gurdwaras, temples and a mosque. Even today, the people of Sri Hargobindpur visit all these places frequently and freely, regardless of their religious affiliations.

Quotes

Tying bonds of unity at Guru ki Maseet By Anna Bigelow report from the Tribune

Guru ki Maseet in Sri Hargobindpur

As the light in the gurdwara courtyard grew golden, an unusual meeting took place between Baba Kirtan Singh, head of the Nihang Taran Dal in Baba Bakala, and Dr Mohammad Rizwanul Haque, Secretary of the Central Wakf Council, Delhi. The two men sat facing each other on simple string charpoys to discuss their shared interests in a masjid built by a Sikh Guru.

It was like observing master weavers at work as they interlaced two of the many threads that make up the rich tapestry of India’s religious and cultural fabric. Dr Haque sat leaning forward, listening raptly in order to make out the wavering but urgent voice of the elderly Sikh.

Baba Kirtan Singh had come prepared, bringing with him several texts of Sikh history, some written in Gurmukhi and others in Persian script. He read from the records about the Sikh Guru’s conversion of the house of a dead Muslim into a masjid and the setting up of a langar for the poor. He also told of an encounter between Guru Nanak and some Muslims that ended with the declaration that "if Hindus are the left hand, then Muslims are the right, and we all believe in the one true God." In this way, Baba Kirtan Singh skillfully wove together the history of the Gurus and the present situation, the preservation and maintenance of a place — the Guru ki Maseet in Sri Hargobindpur— that is precious to both the communities.

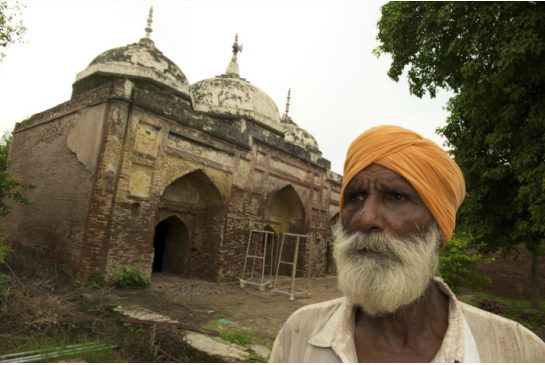

The maseet is picturesquely situated on a hill overlooking a curve in the mighty Beas river. After coming to the region in the early 17th century, Guru Hargobind built temples, gurdwaras, and a masjid to accommodate the spiritual needs of all the inhabitants. Since Partition there has been no Muslim population in the area. In the intervening years, the care of the site was taken up by Nihangs sent by Baba Kirtan Singh from his base in Baba Bakala, some 20 kilometres away. The present sevadar, Baba Balwant Singh, has been at the site since 1984, clearing weeds, sweeping dust, preparing langar, and fulfilling all the other obligations of his faith in service to the Guru, his Baba, and the Sikh tradition.

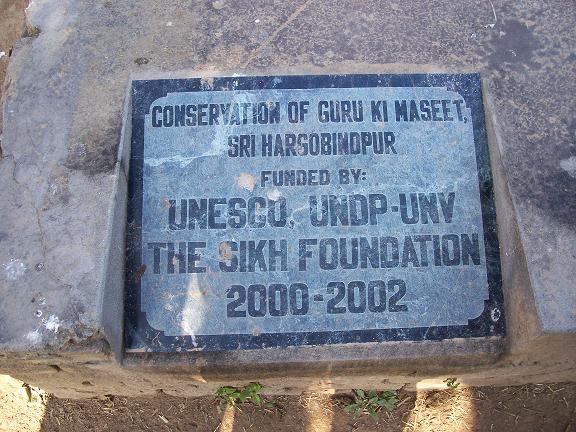

In 1997, a survey team with the Cultural Resource Conservation Initiative (CRCI) came to the town and saw the maseet. Recognizing the value of the building, the group began to undertake the restoration of the mosque as part of the UNESCO and UNDP-UNV’s "Culture of Peace" programme, and with additional financial support from the US-based Sikh Foundation.

However, some hurdles had to be cleared. The area around the maseet had been encroached upon, the hillside was eroding and needed shoring up, and the local residents seemed largely unaware of this unique treasure and were not entirely comfortable with the Nihang presence at the site. Furthermore, a bir of the Guru Granth Sahib had been placed within the mosque and a Nishan Sahib erected near it, making the building’s identity as a maseet questionable.

As the restoration work began, the encroachment was cleared and the land cleaned up. A neighbour donated a piece of land and further property was purchased by CRCI with the assistance of UNESCO and the Sikh Foundation. Local residents contributed their time and energy to the site by organising a large seva with a langar that brought people from the entire region to the maseet — to see it, learn about it, and help it survive. People who had initially been skeptical or even afraid of the Nihangs began to learn about their beliefs and practices and now frequently and unhesitatingly visit the site to see the progress of the project.

Finally, a new space was built and the Guru Granth Sahib was moved out of the maseet. Various officials from the local Wakf Board, members of the SGPC, MLAs and Members of Parliament have visited the maseet and responded to queries from members of their communities who wished to know about the status of the site. All of these events culminated in the meeting on February 8 between Dr Haque and Baba Kirtan Singh in order to determine the future of the Guru ki Maseet.

The white-bearded elderly man in the blue and white turban sitting on one charpoy with his pile of books lovingly wrapped in cloth contrasted sharply in appearance, age and religion with the much younger, clean-shaven man in western clothes perched across from him. Yet at this meeting their unity of purpose and the similarity of their thinking was equally apparent.

Seeking common ground, Dr Haque had traveled a long and bumpy road from Delhi to Punjab to find Baba Kirtan Singh at his gurdwara. Baba Kirtan Singh had also made a long journey -- into the annals of Sikh history to discover precedents from the past that would strengthen the bonds of the two communities. The two men made great efforts to understand each other, to hear and be heard as they discussed the ways in which both communities could simultaneously live up to their interest and obligations to preserve and maintain the Guru’s maseet. They were helped in speaking to each other across languages and traditions by the translations of Punjab Wakf Board CEO Ikhlaq Ahmad Khan and CRCI Director Gurmeet Rai. As the conversation proceeded in Punjabi, Hindi and Urdu, the matter was clarified and an understanding reached. The Guru had built a masjid.

As Baba Kirtan Singh put it, "This maseet was established by our Guru. It is a maseet, but it is as important to us as a gurdwara." Dr Haque echoed this sentiment, declaring, "Your Guru built a maseet and it was his intention that Muslims come and perform namaz there. There are no Muslims now, but you (the Nihangs) have been preserving it very well and we all want it to stay in its original form." Later Baba Kirtan Singh stated that just as Muslims testify to the oneness of God, Sikhs say Sat Sri Akal. He again assured Dr Haque and the other representatives from the Wakf Board that they should not worry at all, the building would be kept as a maseet, as the Guru had wanted.

If the Guru built a mosque, it should be understood as more than a conciliatory gesture towards the other community. It was an act of community-building by a leader whose Miri-Piri sensibilities were steeped in the devotional traditions of Nanak, Baba Farid, Kabir and Namdev. The masjid is not simply a place sacred in various ways to these separate religions. It is an important symbol of the integrated past and present of India’s cultural heritage.

The maseet as a Muslim space also represents the deeply held principles of equality in Islam. This value is visible in the structure of the mosque itself. The horizontal orientation maximizes the proximity of the faithful to Mecca. It is further evident in the accessibility of the space to all people. Everyone is welcome here in a space that is designed to reflect the oneness of God and the importance of community. There is no rule in Islam against the participation of non-Muslims in the care of a Muslim shrine. On the contrary, there are countless precedents for the collective custody of such places. The only rules pertaining to who may or may not enter a masjid, or for that matter a gurdwara, are rules of adab, or correct conduct, by which one shows respect to God, the place, and the assembled people, and oneself by entering in a state of bodily cleanliness with a covered head, bare feet, and a reverent attitude.

The crucial lesson to learn from this encounter is that these two leaders made deliberate and sincere efforts to meet each other, and to forge, rather than sever, the bonds between their two communities. Instead of seeking precedents and principles that would establish priority of their own claims and interests in the property, both strove to find the events and ideas of the past that would support their sharing of the maseet’s maintenance. In this way they established that sharing the responsibilities that both groups want to assume in the future care of the mosque is a fulfillment of the principles of their faiths. They further demonstrated that this joint project was simply one more example of India’s proud heritage of pluralism.

With the leadership of people like Dr Haque and Baba Kirtan Singh and the support of the Muslim and Nihang communities, neighbours, visitors, and benefactors, the Guru ki Maseet has every hope of surviving and providing future generations with yet another historic precedent for their efforts to live together in an increasingly plural and diverse society.

With the sound of the evening rehras permeating the air, providing a soothing sonic background, an agreement to this end was reached — the Guru ki Maseet is a mosque and should remain such, as per the wish of Guru Hargobind. The Nihangs who have cared for and respected the site for so long would continue to oversee its upkeep. The Guru Granth Sahib is in a newly built room at some distance from the maseet.

The locals of Sri Hargobindpur, who take increasing pride in their unique monument, will continue to support the place, doing seva there and executing plans for a community centre with a garden and library. Muslims who come are free to perform namaz. And visitors from all over the world will have the opportunity to see the Guru ki Maseet as a living example of the depth of India’s integration, past and present.

- Above news item appeared on Saturday, February 24, 2001 with thanks to: www.tribuneindia.com

In a historic gesture, Sikhs return mosque to Muslims

"The mosque had been in disrepair for long. Now it has been restored by a group of Sikhs and Muslims in a unique manifestation of India's multi-religious society", says Zafarul-Islam Khan

A new chapter was inked in the Western Indian state of Punjab last week. While large-scale bloodshed continues in Gujarat and several other parts of the country over the issue of the proposed Ram temple construction at the site of the now demolished Babri Masjid amid extremist demands to surrender "thousands" of other mosques, a historical mosque was returned to Muslims by the Sikh community. For the last fifty four years since Partition of the country this mosque, known as "Guru ki Maseet" (Guru's Mosque) was being used as a gurdwara (temple) by the Sikh community. The mosque is picturesquely situated on a hill overlooking a curve on the banks of the mighty Beas river in Punjab's Gurdaspur district.

Maulana Hamid Husain Qasmi, the imam of the Jama Masjid in Amristsar, the largest city of the state, was specially called to lead the first prayers in the mosque on March 23. The mosque was constructed by Guru (Sikh religious leader) Hargobind Singh 370 years ago. According to Sikh tradition, the Guru had converted the house of a dead Muslim into a masjid and set up a langar (common kitchen) for the poor. Their tradition records an encounter between Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru, and some Muslims which ended with the declaration that "if Hindus are the left hand, then Muslims are the right, and we all believe in the one true God."

A “memorandum of understanding” (MoU) has been signed by the Nihangs, the Sikh caretakers of the mosque, and the Punjab Waqf Board. Dr Mohammad Rizwanul Haque, Punjab Waqf Board Administrator, described the MoU as an international event which would pave the way for strengthening communal harmony in the country.

Ms Gurmeet Rai, director of the Cultural Resource Conservation Initiative (CRCI), who was honoured with an international award by UNESCO for the conservation of the historical Krishan Temple at Kishankot village and who has been in the forefront of the campaign for the restoration of the mosque to Muslims said that though as per the MoU, the Taruna Dal, a sect of Nihangs, has agreed to conserve “Guru ki Maseet” as a traditional mosque by allowing Muslims to perform prayers there, yet the Waqf Board requested the Nihangs to continue as caretakers.

For many years, this mosque has been maintained by the Nihangs as it was abandoned at the time of the Partition. Dr Haque said he remembered that the late Baba Kirtan Singh, the Nihang chief of the Taruna Dal, had signed an MoU at Baba Bakala on February 8 last year. He said it was the desire of the Baba that Muslims must perform their prayers at the mosque which was gifted to them. As per the wishes of Baba Kirtan Singh, five saplings were planted in the names of the Sikh Gurus.

The mosque had been in disrepair for long. Now it has been restored by a group of Sikhs and Muslims in a unique manifestation of India's multi-religious society. Sikhs offered their labour, Muslim masons repaired the walls and an all-woman team of restorers led by Ms Gurmeet Rai lent its expertise.

In 1997, a survey team of the CRCI came to the town and inspected the mosque. Recognizing the value of the building, the group began to undertake the restoration of the mosque as part of the UNESCO and UNDP-UNV’s "Culture of Peace" programme, and with additional financial support from the US-based Sikh Foundation. A neighbour donated a piece of land and further property was purchased by CRCI.

Finally the work of restoration of this 370-year-old mosque built by Guru Hargobind, the sixth Guru of the Sikhs, was completed on March 23 in the town named after him, Sri Hargobindpur, halfway between Jalandhar and the Sikh's holy city of Amritsar, in India's western province of Punjab. The "Guru Ki Maseet" was built in 1630 after the Guru Hargobind's battle with Jalandhar's ruler, Abdullah Khan. Legend has it that the mythical Hindu god Vishwakarma came down to earth in a human form to build this sacred town.

Why did a Sikh Guru build a mosque? Had it been a dharmshala (a rest house for Hindu pilgrims), it might have been destroyed by invaders. By building a mosque, and that too by a Sikh Guru, it was ensured that people of all religions would protect it, Baba Kaladhari, a spokesman for the Sikhs, said.

No one destroyed it, yet not too many looked after it either. The neglect began with the Subcontinent's Partition, when Muslims of the area migrated en masse to Pakistan. 'The mosque was deserted for a few weeks, no prayers were held. Then someone installed in the mosque a copy of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book, and started taking care of not just the mosque but also treating the sick, Chandigarh's Tribune newspaper quoted Mohinder Kaur as saying. She was 18 at the time of Partition in 1947 and still lives a few yards from the shrine.

For Ms Gurmeet Rai and her team, beginning restoration work wasn't easy. The Nihangs (praetorian Sikh guards), who had taken control of the mosque in the mid-1970s, weren't keen on anyone tampering with what they considered to be the Sikh Guru's own work.

'When Rai first approached them with the idea of restoration, the response of the Nihangs was very simple - take care not to damage the shrine, and do not ask us for any money.

The enthusiasm has been contagious since the work on the restoration of the mosque was initiated a year ago. The entire village, and even those from the surrounding areas, answered Rai's call for clearing the earth around the shrine. Hundreds of school children and Nihangs did the spadework. Today the mosque stands elevated. "We will now try and remove all later additions, like cement, plaster and white-wash from the brick structure, and then apply lime paste plaster, which will allow the building to breathe," Rai says.

The performance of Muslim religious prayers in the mosque after 55 years would be recorded in history as an event when Sikhs showed so much magnanimity towards Muslims, said Dr Mohammed Rizwanul Haque. Last year, Waqf Board officials approached the Sikhs requesting them to hand over the mosque. The Sikhs finally agreed after a series of meetings.

The mosque is not the lone case that was under Sikh control. After the Partition of undivided India, Muslims who were in majority in the area, left for Pakistan. Hundreds of mosques were left unattended. Now these mosques have either been destroyed by savagery of times or are under personal control of people who later occupied them. Sikh community meanwhile has been very generous in vacating such mosques when approached by any Muslim group or Punjab Waqf Board that looks after Muslim Waqf properties in three north Indian states of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Haryana.

In a similar event a year ago Sikhs of Chahar Mazra village in Ropar District built a mosque for their Muslim neighbours. Sant Varyam Singh, who heads Vishwa Gurumat spiritual mission in the adjacent Ratwara Saheb village, built the mosque for the Muslims of the area. The first prayers were offered on the Eid day in March last year. After the prayers there were heart-warning scenes of celebrations, exchange of Eid greetings and Muslims embracing their Sikh brethren.

After Partition in 1947, most Muslims of this village migrated to Pakistan and only about 15 households were left in Chahar Mazra who resolved to live and die there. There was no mosque in this village. These Muslims were poor labourers who could not build a mosque for themselves and all these 53 years since 1947 they had to travel 10 to 15 kms away for offering prayers.

When Sant Varyam Singh built his Ashram (religious retreat) in Ratwara Sahib, he stated a movement against drunkenness in the area. During this process he came across these Muslims who helped his movement and offered their services for his Ashram. Sant Varyam Singh visited USA where Ali Faryad, an Iranian at Stratford University, offered a donation for his Asharam. But instead of using this amount for the Ashram, the Sant decided to use it for building a mosque for the Muslims of Chahar Mazra. A site was chosen and construction of the mosque started. The Sant himself laid the foundation stone of the mosque in December 1999.

When the mosque was completed, Sant Varyam Singh left it to the Muslims when to inaugurate it. They decided that they will inaugurate it by offering Eid prayers. Captain Kanwaljeet Singh, the then Punjab finance minister, handed over the mosque to the Muslims on that day.

- Above News item appeared on April 6, 2002 with thanks to www.milligazette.com

Unifying Structures: Sharing the Guru's Mosque

In the mid-seventeenth century the sixth Sikh Guru, Hargobind, is widely believed to have built a mosque for the Muslim population of a settlement now called Sri Har- gobindpur on the river Beas in Punjab, India. Hundred years later the Muslim residents departed during the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, and the site fell into disuse for some years. Sometime in the mid 1980s, a group of Nihang Sikhs came to claim the building and care for it, regarding it as a sacred duty, given that their revered Guru had ordered its construction.

They cleaned it up, raised a Sikh banner out front, and placed a copy of the Sikh scripture called the Guru Granth Sahib in what had formerly been the qibla, marking the direction of Mecca. This effectively converted the Guru ki Maseet (Guru's Mosque) from a disused mosque into an active gurdwara, or Sikh place of worship. No Muslims lived in the town at the time, and initially no one objected. Then in 1997, a heritage restoration organization called the Cultural Resource Conservation Initiative (CRCI) came upon the old mosque. They noted its architectural value, heard its story, and targeted the deteriorating structure for conservation. In the fall of 2000, publicity about the project brought the building to my awareness as I was in India studying shared sacred sites and interreligious relations.

The publicity also caught the attention of the Punjab Waqf (Muslim religious endowment) Board, which was the legal owner.The Waqf Board and other concerned Muslims raised objections to the Sikh presence and usage of the site. Eventually negotiations took place, resulting in a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which agreed to share the maintenance of the site between the Sikhs and the Punjab Waqf Board, with the heritage group CRCI functioning as mediators and midwives to the process.

Among the many unusual features of the memorandum is the tenth stipulation stating that "social practices that can fracture the structural unity of the site and the building will be disallowed within the complex.

Significantly, in the view of the architects of the agreement, the "structural unity" of the mosque known as the Guru ki Maseet does not merely refer to the bricks and mortar that constitute the building itself. Quite the contrary, the three main parties to the MOU agreed that "structural unity" is defined as the physical structure which includes the building and its precincts and the social cultural values associated with it. These values include the message of the historic building, namely the promotion of the peace and harmony between different religious faiths by means of participation and sharing responsibility.

Such language in the agreement was carefully forged over several drafts executed by the three parties to the MOU: the Nihang Sikh jatha (band), the Punjab Waqf Board, and CRCI, the heritage conservation group based in Delhi. This story illuminates the production, conversion, reconversion, and ultimate transformation of a contested space into a unifying structure. The negotiations constituted a complex process through which the parties involved generated a definition of the mosque as a shared site and affirmed all three groups as having legitimate interests in caring for it. This challenges the usual assumption that mosques are exclusively Islamic spaces. In this case, through affirming the site as a mosque, the Guru's intention in building it was also affirmed, giving the Nihangs and the Waqf Board common ground. Furthermore, bolstered by their willingness to pursue a cooperative arrangement, the Guru ki Maseet's role as a unifying site was given historical roots through a range of practices engaged at all levels of the constituent community. The negotiations over the final agreement revealed a subtle mutual attunement of language and the accommodation of conflicting practices in a highly charged political context. In particular, close attention to the process through which the final MOU's language evolved shows how a shared conceptual space was laboriously created to sustain the joint management of a shared physical and social space.

The saga of the Guru ki Maseet is bound up with many highly charged issues: population shifts, Partition history, minority religious identity, religion and politics, heritage conservation, conflict resolution, and the sharing of sacred space. An exam- ination of the most intense phase of negotiations over the site's identity in the spring of 2001 indicates that the resolution of the multiple claims to the Guru ki Maseet did not require that a single understanding of the site become dominant, eliminating other claims or suppressing variant usages of its space. On the contrary, the shared site came to embody what the phenomenologist of space Edward Casey identifies as the unique ability of a place to contain without conflict the most diverse elements that constitute its being. This raises interesting possibilities for transforming contestation into cooperation.

The Guru ki Maseet is generally believed to have been built by the sixth Sikh Guru Hargobind. His father, the fifth Guru Arjan, founded Sri Hargobindpur in 1587. According to local lore, at some point in the early-to-mid,"seventeenth century Guru Hargobind came to the town to spend a rainy season due to the settlement's advantageous situation on high ground looking over the Beas River. According to tradition, the Hindu god Visvakarma descended to earth to help in the construction of fortifications, completing them in seven days.

The town's design included gathering places for the Guru's followers, Hindu temples, and the Muslim mosque. At this point the Sikh tradition was still taking shape, and among the Guru's followers were Hindus and Muslims who clearly felt no compulsion to convert. Therefore, when Guru Hargobind settled in this spot, he felt it necessary to provide for the spiritual needs of the whole company. The building of a mosque was an especially important gesture as Guru Hargobind, his followers, and his allies (some Muslim) were increasingly in conflict with the Mughal authorities. Though the Guru moved on, the mixed population remained until the Partition of 1947 split Punjab in two and divided the population along religious lines. Most Muslims in East Punjab moved west to Pakistan, and Hindus and Sikhs in the west shifted to the Indian side of the new border. This rupture involved the kind of violence that impacted nearly every part of the region, leaving memories and shaping identities that endure to this day. Since Partition there have been no Muslims among Sri Hargobindpur's four thousand residents, and hence no Muslim worship took place in the mosque for over fifty years.

Muslim lands and buildings abandoned in 1947 became the property of the Punjab Waqf Board, the state bureau of the Central Waqf Council based in New Delhi. Waqf agencies oversee Muslim charitable endowments and Muslim properties such as graveyards, mosques, schools, shrines, hospitals, and any other property that has been given in perpetuity for the benefit of the community, both Muslim and non-Muslim. Particularly in Punjab, where the fewest Muslims remained, Muslim structures were often taken over by the local population or an influx of refugees from the west. Some properties were eventually reclaimed, but many were not. Some sites were maintained for their original use by non-Muslims. This is especially the case with many tomb shrines, called dargahs in South Asia. At several dargahs in Punjab, Sikh and Hindu caretakers now facilitate the worship of mostly non-Muslim pilgrims to these places. In some situations the Muslim families who had maintained the shrines explicitly asked neighbors to take over when they left; in other cases the supervisors are self-appointed. Many lapsed Muslim properties were allocated to migrants, and in some cases there have been conflicts between the Waqf Board and the local non-Muslim population.

The politics of these lapsed properties are complex. For the Waqf Board and the Muslim population of Punjab, the sight of mosques turned into barns or homes is distressing and at times leads to legal action against the occupants.

In other places it is not worth the effort to evict the new occupants. A former head of the Punjab Waqf Board told me of a program that had been in practice when he was younger for asserting Muslim ownership. He himself had taken up residence at a disused mosque in an agricultural district from which nearly all Muslims had departed. He stayed in the place in order to offer the five-time daily prayer and strengthen the Waqf Board's claim to the site. For the minority Muslim population in India, this is an important identity issue and a matter of community pride, and so, even if they are not in active use, such properties are zealously defended. Muslims have been especially sensitive to threats to their property since 1992, when Hindu extremists tore down the sixteenth-century Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. Furthermore, state and national politics further complicated the situation as from 1999 to 2004 the Hindu nationalist party (the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP) was in power at the national level and a Sikh nationalist party (the Shiromani Akali Dal, or SAD) was in power in the state. Although the absence of Muslim residents in Sri Hargobindpur somewhat simplified the negotiations, this was offset by complications rising from the notoriety among Punjabi Muslims and its coverage in the Indian Muslim press. Furthermore, the negotiations over the Guru ki Maseet took place not long after a mosque elsewhere in Punjab had been destroyed, reportedly by Hindu nationalists. Indeed, when the head of the Central Waqf Council came to visit the Guru ki Maseet and negotiate with the Nihang leader, he proceeded from that meeting to the site of the demolished mosque to investigate.

These events increased Muslim sensitivity about the ownership and usage of sacred space, making the eventual resolution of the situation even more significant. Thus the contestation over the Guru ki Maseet ramified within and beyond Punjab since the politics of religion in India at the time were particularly tense. These conditions overshadowed the prospects of sharing the space. The conservation of the mosque at this juncture demanded a considerably broader approach than merely renovating the building. It required an integrative philosophy designed to unify the structural integrity of both the building and the community in which it was located by facilitating the connections between the mosque and the community, as well as between the Nihangs and the Waqf Board.

So it was that in 1997 a survey team with CRCI came to the town and saw the Guru ki Maseet. Recognizing the significance of the building, the group began to undertake the restoration of the mosque as part of a program sponsored by the United Nations (UN) called Culture of Peace, which was a joint venture between UNESCO, the UN Development Project (UNDP), and the UN Volunteers program (UNV). The UN assisted financially and also sent volunteers to help with both architectural restora-tion and social development work. Additional financial support was obtained from the U.S.-based Sikh Foundation. After the financing for the first phase was secured, the next hurdles were local. The area around the Guru ki Maseet had been encroached on by neighbors, and the hillside was eroding. Furthermore, the local residents seemed largely unaware of this unique treasure and were not entirely comfortable with the Nihang presence at the site. But as CRCI's director Gurmeet Rai pointed out, "all too often the physical condition of a building does not reflect the depth of the bond between a site and the community surrounding it."

Therefore, in conjunction with the work on the mosque, CRCI worked to reestablish these links between the site, the history it symbolizes, and the citizens of the town. CRCI's approach to these chal- lenges was multifaceted. Rather than bringing in a skilled workforce from outside Sri Hargobindpur, local laborers were trained in the techniques required to work on the structure. Since many local men were leaving town to work as truck drivers or laborers elsewhere in the state, hiring residents helped to integrate the community into the project because its members saw the project's potential in terms of labor and potentially in terms of tourism. Additional strategies for integration included approaching neighbors and giving them an opportunity to learn about the site, to share their own knowledge, and to meet Balwant Singh, the Nihang care-taker. CRCI also initiated a project in the local schools to connect children to the history of their town. Along with educational programs and oral history projects that recorded memories about the town and its sacred sites, the UNV and CRCI workers engaged in a constant circuit of visitation around the town. Visitors were always welcome at the site. This rendered CRCI's work transparent to the local community.

This availability and honesty built trust in the town that CRCI was not simply trying to commandeer their cultural heritage. Through these multilayered efforts and trust-building measures the majority of Sri Hargobindpur residents came to know of the restoration project and consider it a positive addition to the community.

As the restoration work began, the encroachment was cleared and the land cleaned up. A neighbor donated a piece of land and additional property was purchased by CRCI. Having gained trust and interest in the project, residents began to get involved in the physical labor of conservation. They contributed their time and energy to the site by organizing a large seva. Seva, meaning service, is a central element of Sikh religious practice. The Sikh Gurus placed a high premium on behavior that strengthened the community by improving the conditions of life for all. Seva is also a way of generating and promoting egalitarianism as everyone serves and is served by others. No one's labor counts more than anyone else's. In Sri Hargobindpur, the goal of the seva at the Guru ki Maseet was to remove debris and vegetation from the land around the mosque. Mobilized by CRCI and by community leaders, people from all over the area came to the mosque's seva.

People who had initially been skeptical of the project or afraid of the Nihangs began to learn about their beliefs and practices and now frequently and unhesitatingly visited the site to see the progress of the project.

The seva and other efforts of CRCI to be open and transparent clearly paid dividends, as did the program to educate the community about the Guru ki Maseet. Yet the population that was connecting with the Guru ki Maseet was also entirely non-Muslim. Although both Hindu and Sikh residents revere the structure as part of the Guru's legacy, the Islamic dimension of the building was not a part of their collective identity and only the elderly had memories of its use as a mosque. In preserving the structure and reintegrating it into the life of Sri Hargobindpur, CRCI also inadvertently intensified the non-Muslim elements of the structure.

Playing up the Guru's role and waging an educational campaign to raise awareness of this history solidified the bond between the building and the community. Sri Hargobindpur began to feel proprietary about the Guru ki Maseet. This was perhaps most evident in the way in which the mosque had been effectively converted into a gurdwara. When Baba Balwant Singh came to the mosque, he placed a copy of the Guru Granth Sahib in the mosque and erected a Nishan Sahib (a staff bearing the Sikh standard) outside. These markers of Sikh sacred space brought the building's identity as a mosque into question. Although places, as Casey has argued, may be uniquely able to contain contradictory meanings, in some cases the multiple identities of a place actually conflict and cannot be contained. This became apparent after articles appeared in several national news- papers about the Guru ki Maseet and CRCI's efforts.

The publicity brought a challenge to the progress of the restoration and to the Nihangs role as caretakers. A prominent Muslim activist and former member of parliament, Syed Shihabuddin, heard about the restoration from these newspaper accounts and raised objections. Shihabuddin had long been concerned about the co-optation of Muslim sacred sites by non-Muslims. He was a key figure in the Babri Masjid Action Committee and in legal efforts to restore that mosque at Ayodhya after it was destroyed by Hindus in 1992. No doubt because of his involvement in the Ayodhya dispute, which remains a thorny problem for India's Hindus and Muslims, Shihabuddin was on the alert. Dismayed by reports of what appeared to him as yet another case of Muslim property being usurped by non-Muslims in a place in which few Muslims lived and could defend their legal ownership, Shihabuddin lodged a complaint with the United Nations Committee on Human Rights (UNHRC), as well as notifying the Waqf Council. Waqf Board representatives visited the site. The police were called to take statements from CRCI and locals about the mosque's history and status. The situation became tense, and the site that had been heralded as evidence of India's rich, plural culture was in danger of becoming another example of politicized religion and communal conflict. Recognizing their failure to include the Waqf Board as legal owners or any Muslims in the conservation process, CRCI and Sri Hargobindpur community leaders began the arduous process of overcoming their own missteps and the mistrust between the parties. Several measures were taken to give the Waqf Board and the Muslim minority a stake in the mosque and its symbolic role as a multiconfessional site. First, a new structure was built away from the Guru ki Maseet, and the Guru Granth Sahib was moved. On the invitation of CRCI and the local community, various officials from the Waqf Board, members of the SGPC (the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee, which oversees gurdwaras), members of the legislative assembly, and at least one member of parliament all visited the mosque. Each of these visitors had concerned constituents who felt they had a stake in the identity of the Guru ki Maseet. While the SGPC did not press a claim to the mosque, it was interested in how all sites associated with the Sikh Gurus were maintained. These visits assuaged their fears and gave them resources with which to address queries from members of their constituencies who wished to know about the status of the site. But, as the Nihangs wished to continue their seva at the mosque and the Waqf Board wished to reestablish its proprietary rights, these roles needed clarification. To resolve these potentially conflicting claims, a meeting took place on February 8, 2001, between the Secretary of the Central Waqf Council, Dr. Mohammad Riz- wanul Haque, and the jathedar or head of the Nihang Tarna Dal (Baba Bakala), Sant Baba Kirtan Singh, to determine the future of the Guru ki Maseet.

The meeting ended with everyone feeling that a cooperative arrangement was within reach.

The final memorandum, written in both Punjabi and English, was signed in November of 2001.

CRCI's overriding interest was in the physical and sociocultural structure of the maseet in its broader context. Through the conservation they sought to fulfill their mission to reintegrate the community with its own heritage. For the Nihangs it was crucial that the original spirit and structure of the mosque be preserved as intended by Guru Hargobind and that they be able to continue in their role as caretakers. For the Waqf Board, the right of ownership, even in absentia, was essential, and its leader- ship did not wish to relinquish that ultimate authority. Yet they, too, saw the value of promoting the site as an emblem of interreligious cooperation, especially in the absence of Muslims who might have wished to use the mosque for regular prayer. The final MOU incorporated these concerns. It opened with the declaration that Guru Hargobind "conceptualized this Maseet as a symbol of peace and unity between the Sikhs, Muslims and the Hindus, and remarked that "this Maseet is described as sanjhi walda [shared sacred space]. It went on to acknowledge the Nihangs care for the abandoned site. The placing of the Guru Granth Sahib in the mosque was explained thus: "The Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book of the Sikhs, was placed inside the Maseet by the Nihang Sikhs due to the association of the Maseet with the sixth Sikh Guru, Guru Hargobind. The sanctity of the Maseet was always maintained in keeping with the secular traditions of India. This is a matter of pride.

The Memorandum of Understanding was formally celebrated with a cere- mony on April 23, 2002, when namaz was performed for the first time since 1947 at the Guru ki Maseet. The imam of the Jama Masjid in Amritsar, Maulvi Hamid Hussain Qasmi, came, and a representative group of Muslims prayed together in front of the building, surrounded by the Nihangs and community members.

In the News

In India’s Punjab, a rebuilt mosque stirs hope

As a daily labourer in this lush stretch of rich, loamy farmland, Ganga Singh has spent most of his life helping to build schools, hospitals and other local buildings.

SRI HARGOBINDPUR, INDIA—As a daily labourer in this lush stretch of rich, loamy farmland, Ganga Singh has spent most of his life helping to build schools, hospitals and other local buildings.

For the past few months, the 75-year-old has worked on a most unusual project: Singh is among a group of local Sikhs who is helping to restore a 350-year-old mosque.

Located on a nondescript side street in Sri Hargobindpur, a city of 13,000 that’s a two-hour drive from the Pakistan border, the mosque — Guru Ki Maseet — was originally constructed in 1637 by Guru Hargobind, the city’s namesake.

One of the most revered figures in the Sikh religion, Guru Hargobind built it for the local Muslim community at the same time as the Taj Mahal was being constructed in central India. But in 1947, the Guru Ki Maseet was ransacked and fell into disrepair after Muslims living here migrated to Pakistan following partition.

Nowadays, there are about 15 Muslim families living in Sri Hargobindpur and the closest operable mosque is an hour’s drive away.

Besides preserving what is arguably an archaeological site, the repair means Muslim families here will have a place of worship within walking distance. A Sikh foundation in the U.S. has contributed $20,000 for the project, with the Punjab state government adding another $88,000.

“I think if Gandhi could see this he would pat us on the back,” said Harjeet Bhalla, 60, president of Sri Hargobindpur’s municipal council.

“Ours is a multilingual, multi-religious country so it’s important that we do this.”

Several locals say they hope the project sends a message beyond this remote farming community.

Although India has enjoyed an economic boom in recent years, parts of the country remain paralyzed by violence. Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state, is convulsing after a series of recent deadly protests, and development in several other states has been hobbled by a Maoist insurgency.

“This mosque sends a message to the rest of our country that everyone should be able to live together,” said Rahul Vij, a 22-year-old Hindu living in Sri Hargobindur.

The rebuilt Guru Ki Maseet might help establish closer ties even within this community, where some Sikh and Hindu residents had no idea about a Muslim enclave just 10 minutes away. (Maseet is the Punjabi word for masjid, or mosque.)

Lounging on a bamboo charpoy near the mosque, 50-year-old Sikh priest Baba Balwant Singh said confidently that there was “not a single” Muslim in Sri Hargobindpur.

“Maybe they will come, who knows?” he said, wearing a deep blue turban and matching clothes.

Manjeet, a 13-year-old Hindu boy who hovered around the mosque construction, said he’d never met a Muslim before.

“They must be the same as us?” he asked.

The mosque in Sri Hargobindpur looks its age.

The Urdu script above its entrance is fading and the walls are cracked, leaving bricks exposed and crumbling. While some of the floral decorative motifs inside are still vivid, some sections have flaked away over time.

A few blocks away from Sri Hargobindpur’s main bazaar, 45-year-old Halima worked with her four children to apply a coat of mud on a small hut made of straw and cow dung. Her husband Babu was busy grazing the family’s few buffalo in nearby field.

Halima, who is Muslim and who uses one name, said she couldn’t recall the last time she’d been to a mosque. Her husband goes every Friday, but cannot afford the bus fare for his wife and kids.

Dusting off a floor in her haggard tin-roofed home, Halima showed visitors her red and black prayer mat.

“I’m illiterate but I’m very happy to talk to you about this,” Halima said, adjusting her green shawl and lifting up her hands as if in prayer. “The bus ride to the mosque costs 20 rupees (50 cents) so that not something I can afford. It will be nice to go to mosque. And maybe we will get an imam.”

Muslims offering prayers in the Guru's Mosque while Sikhs watch them

The mosque had been in disrepair for long. Now it has been restored by a group of Sikhs and Muslims in a unique manifestation of India's multi-religious society, says Zafarul-Islam Khan

New Delhi, April 6: A new chapter was inked in the Western Indian state of Punjab last week. While large-scale bloodshed continues in Gujarat and several other parts of the country over the issue of the proposed Ram temple construction at the site of the now demolished Babri Masjid amid extremist demands to surrender "thousands" of other mosques, a historical mosque was returned to Muslims by the Sikh community. For the last fifty four years since Partition of the country this mosque, known as "Guru ki Maseet" (Guru's Mosque) was being used as a gurdwara (temple) by the Sikh community. The mosque is picturesquely situated on a hill overlooking a curve on the banks of the mighty Beas river in Punjab's Gurdaspur district.

Maulana Hamid Husain Qasmi, the imam of the Jama Masjid in Amristsar, the largest city of the state, was specially called to lead the first prayers in the mosque on March 23. The mosque was constructed by Guru (Sikh religious leader) Hargobind Singh 370 years ago. According to Sikh tradition, the Guru had converted the house of a dead Muslim into a masjid and set up a langar (common kitchen) for the poor. Their tradition records an encounter between Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru, and some Muslims which ended with the declaration that "if Hindus are the left hand, then Muslims are the right, and we all believe in the one true God."

A “memorandum of understanding” (MoU) has been signed by the Nihangs, the Sikh caretakers of the mosque, and the Punjab Waqf Board. Dr Mohammad Rizwanul Haque, Punjab Waqf Board Administrator, described the MoU as an international event which would pave the way for strengthening communal harmony in the country.

Ms Gurmeet Rai, director of the Cultural Resource Conservation Initiative (CRCI), who was honoured with an international award by UNESCO for the conservation of the historical Krishan Temple at Kishankot village and who has been in the forefront of the campaign for the restoration of the mosque to Muslims said that though as per the MoU, the Taruna Dal, a sect of Nihangs, has agreed to conserve “Guru ki Maseet” as a traditional mosque by allowing Muslims to perform prayers there, yet the Waqf Board requested the Nihangs to continue as caretakers.

For many years, this mosque has been maintained by the Nihangs as it was abandoned at the time of the Partition. Dr Haque said he remembered that the late Baba Kirtan Singh, the Nihang chief of the Taruna Dal, had signed an MoU at Baba Bakala on February 8 last year. He said it was the desire of the Baba that Muslims must perform their prayers at the mosque which was gifted to them. As per the wishes of Baba Kirtan Singh, five saplings were planted in the names of the Sikh Gurus.

The mosque had been in disrepair for long. Now it has been restored by a group of Sikhs and Muslims in a unique manifestation of India's multi-religious society. Sikhs offered their labour, Muslim masons repaired the walls and an all-woman team of restorers led by Ms Gurmeet Rai lent its expertise.

In 1997, a survey team of the CRCI came to the town and inspected the mosque. Recognizing the value of the building, the group began to undertake the restoration of the mosque as part of the UNESCO and UNDP-UNV’s "Culture of Peace" programme, and with additional financial support from the US-based Sikh Foundation. A neighbour donated a piece of land and further property was purchased by CRCI.

Finally the work of restoration of this 370-year-old mosque built by Guru Hargobind, the sixth Guru of the Sikhs, was completed on March 23 in the town named after him, Sri Hargobindpur, halfway between Jalandhar and the Sikh's holy city of Amritsar, in India's western province of Punjab. The "Guru Ki Maseet" was built in 1630 after the Guru Hargobind's battle with Jalandhar's ruler, Abdullah Khan. Legend has it that the mythical Hindu god Vishwakarma came down to earth in a human form to build this sacred town.

Why did a Sikh Guru build a mosque? Had it been a dharmshala (a rest house for Hindu pilgrims), it might have been destroyed by invaders. By building a mosque, and that too by a Sikh Guru, it was ensured that people of all religions would protect it, Baba Kaladhari, a spokesman for the Sikhs, said.

No one destroyed it, yet not too many looked after it either. The neglect began with the Subcontinent's Partition, when Muslims of the area migrated en masse to Pakistan. 'The mosque was deserted for a few weeks, no prayers were held. Then someone installed in the mosque a copy of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book, and started taking care of not just the mosque but also treating the sick, Chandigarh's Tribune newspaper quoted Mohinder Kaur as saying. She was 18 at the time of Partition in 1947 and still lives a few yards from the shrine.

For Ms Gurmeet Rai and her team, beginning restoration work wasn't easy. The Nihangs (praetorian Sikh guards), who had taken control of the mosque in the mid-1970s, weren't keen on anyone tampering with what they considered to be the Sikh Guru's own work.

'When Rai first approached them with the idea of restoration, the response of the Nihangs was very simple - take care not to damage the shrine, and do not ask us for any money.

The enthusiasm has been contagious since the work on the restoration of the mosque was initiated a year ago. The entire village, and even those from the surrounding areas, answered Rai's call for clearing the earth around the shrine. Hundreds of school children and Nihangs did the spadework. Today the mosque stands elevated. "We will now try and remove all later additions, like cement, plaster and white-wash from the brick structure, and then apply lime paste plaster, which will allow the building to breathe," Rai says.

The performance of Muslim religious prayers in the mosque after 55 years would be recorded in history as an event when Sikhs showed so much magnanimity towards Muslims, said Dr Mohammed Rizwanul Haque. Last year, Waqf Board officials approached the Sikhs requesting them to hand over the mosque. The Sikhs finally agreed after a series of meetings.

The mosque is not the lone case that was under Sikh control. After the Partition of undivided India, Muslims who were in majority in the area, left for Pakistan. Hundreds of mosques were left unattended. Now these mosques have either been destroyed by savagery of times or are under personal control of people who later occupied them. Sikh community meanwhile has been very generous in vacating such mosques when approached by any Muslim group or Punjab Waqf Board that looks after Muslim Waqf properties in three north Indian states of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Haryana.

In a similar event a year ago Sikhs of Chahar Mazra village in Ropar District built a mosque for their Muslim neighbours. Sant Varyam Singh, who heads Vishwa Gurumat spiritual mission in the adjacent Ratwara Saheb village, built the mosque for the Muslims of the area. The first prayers were offered on the Eid day in March last year. After the prayers there were heart-warning scenes of celebrations, exchange of Eid greetings and Muslims embracing their Sikh brethren.

After Partition in 1947, most Muslims of this village migrated to Pakistan and only about 15 households were left in Chahar Mazra who resolved to live and die there. There was no mosque in this village. These Muslims were poor labourers who could not build a mosque for themselves and all these 53 years since 1947 they had to travel 10 to 15 kms away for offering prayers.

The Mosque during restoration

When Sant Varyam Singh built his Ashram (religious retreat) in Ratwara Saheb, he stated a movement against drunkenness in the area. During this process he came across these Muslims who helped his movement and offered their services for his Ashram. Sant Varyam Singh visited USA where Ali Faryad, an Iranian at Stratford University, offered a donation for his Asharam. But instead of using this amount for the Ashram, the Sant decided to use it for building a mosque for the Muslims of Chahar Mazra. A site was chosen and construction of the mosque started. The Sant himself laid the foundation stone of the mosque in December 1999.

When the mosque was completed, Sant Varyam Singh left it to the Muslims when to inaugurate it. They decided that they will inaugurate it by offering Eid prayers. Captain Kanwaljeet Singh, the then Punjab finance minister, handed over the mosque to the Muslims on that day a year ago. q

External Links

- 10-27-12 – The Best Photos of the Week

- Creating History at Hargovindpur

- ‘Namaz’ performed at Guru ki Maseet

- KARTARPUR SAHIB A CORRIDOR TO INTERNATIONAL PEACE

- www.sikhspectrum.com

- www.hinduonnet.com

- www.islamicvoice.com

- In a historic gesture, Sikhs return mosque to Muslims

- Guru Ki Maseet

- THE GURU'S SECULAR CITY