Sikh Temple, Nakuru: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

The history of Sikhs in Kenya’s Rift Valley and its largest town, Nakuru, is long and distinguished. In the early years many worked for the railway, the biggest employer, while others were employed by the Government Public Works Department and by the many European farmers who had settled in the areas towns – notably Elburgon, Gilgil, Londiani, Mau, Narok, Molo Naivasha, Thompson’s Falls and Subukia. | The history of Sikhs in Kenya’s Rift Valley and its largest town, Nakuru, is long and distinguished. In the early years many worked for the railway, the biggest employer, while others were employed by the Government Public Works Department and by the many European farmers who had settled in the areas towns – notably Elburgon, Gilgil, Londiani, Mau, Narok, Molo Naivasha, Thompson’s Falls and Subukia. | ||

When people migrate from one geographical region to another they generally carry with them their cultural and religious values and beliefs. The Nakuru Sikhs were no exception and the fact was recognized in 1903 by the railway authorities who allocated a plot, north of the Nakuru marshalling yards, for the construction of a Gurdwara. As in other cases, most of the early Gurdwara’s in Kenya were built along the route of the railway. | When people migrate from one geographical region to another they generally carry with them their cultural and religious values and beliefs. The Nakuru Sikhs were no exception and the fact was recognized in 1903 by the railway authorities who allocated a plot, north of the Nakuru marshalling yards, for the construction of a Gurdwara. As in other cases, most of the early Gurdwara’s in Kenya were built along the route of the railway. | ||

The first Nakuru Gurdwara soon became a center for regular diwans (assemblies) and for celebrating Gurpurabs (a festive, special occasion) attended by Sikhs from all over the Rift Valley. Many of the European settlers employed Sikhs from all over the Rift Valley. Many of the European settlers employed Sikhs on their farms and held them in high esteem as hard working people with an all-around ability to tackle any job. Most of the Sikhs had technical backgrounds, and were skilled in sawmilling, mechanical engineering, construction, cabinet and furniture making and were also able to thrive under harsh conditions. Lord Delamere, who farmed vast tracts of land around Njoro and Elementetia, employed a number of Sikhs as syces (grooms) and jockeys for his horses which he raced in Nairobi at the old racecourse (which is now known as Racecourse Road in Nairobi City). | The first Nakuru Gurdwara soon became a center for regular diwans (assemblies) and for celebrating Gurpurabs (a festive, special occasion) attended by Sikhs from all over the Rift Valley. Many of the European settlers employed Sikhs from all over the Rift Valley. Many of the European settlers employed Sikhs on their farms and held them in high esteem as hard working people with an all-around ability to tackle any job. Most of the Sikhs had technical backgrounds, and were skilled in sawmilling, mechanical engineering, construction, cabinet and furniture making and were also able to thrive under harsh conditions. Lord Delamere, who farmed vast tracts of land around Njoro and Elementetia, employed a number of Sikhs as syces (grooms) and jockeys for his horses which he raced in Nairobi at the old racecourse (which is now known as Racecourse Road in Nairobi City). | ||

Earlier records indicate that the present plot was acquired on 1st April 1917 and the title registered on 3rd June 1918 in the name of S. Gian Singh, S. Boota Singh, S Wariyam Singh, S. Santa Singh and S. Dausanda Singh as trustees. | Earlier records indicate that the present plot was acquired on 1st April 1917 and the title registered on 3rd June 1918 in the name of S. Gian Singh, S. Boota Singh, S Wariyam Singh, S. Santa Singh and S. Dausanda Singh as trustees. | ||

As the community grew the need for another larger plot was recognized. In 1925, Sardar Sunder Singh was deputed to be the community’s spokesman to the administrative authorities in negotiations for another larger plot. Sunder Singh was an overseer on Keringet Estate in Molo with a number of Sikh artisans working under him. | |||

[[Image:STN3.jpg|thumb|100px|left|S. Sunder Singh, Early Community Spokesman]] | |||

As the community grew the need for another larger plot was recognized. In 1925, Sardar Sunder Singh was deputed to be the community’s spokesman to the administrative authorities in negotiations for another larger plot. Sunder Singh was an overseer on Keringet Estate in Molo with a number of Sikh artisans working under him. He spoke English well, fairly uncommon in those days, and a good communicator and the ideal candidate to present the communities case. A plot, where today’s temple stands, was quickly allocated but the grant brought the Sikh community into dispute with the neighbors. However, with the assistance of the then District Commissioner, Mr. Hobley and the indulgence of Sardar Sunder Singh, the matter was promptly resolved to allow the Sikhs to go ahead with developing their temple plot. | |||

The community stalwarts wasted no time and in about 1926-27 a fully functional and decorated building was completed in three months. The Gurdwara was built with timber framework, clad with corrugated sheets and lined with tounge-and-groove timber and with verandahs on the north, south and west sides and painted throughout. | The community stalwarts wasted no time and in about 1926-27 a fully functional and decorated building was completed in three months. The Gurdwara was built with timber framework, clad with corrugated sheets and lined with tounge-and-groove timber and with verandahs on the north, south and west sides and painted throughout. | ||

The new Gurdwara became the central place of worship and was well attended for every Sikh religious function and celebration. As the area developed agriculturally and commercially the membership increased. The plot was fenced with cedar posts and steel wire interleaved with bamboo splits, or ‘droppers’ and the surrounding grounds were improved. An orchard of lemons, guavas, pawpaws, peaches and pomegranates was established; as there were no restrictions on anyone helping themselves it soon became popular, especially among the children on their way to and from school who would pluck lemons and suck them with great relish. | The new Gurdwara became the central place of worship and was well attended for every Sikh religious function and celebration. As the area developed agriculturally and commercially the membership increased. The plot was fenced with cedar posts and steel wire interleaved with bamboo splits, or ‘droppers’ and the surrounding grounds were improved. An orchard of lemons, guavas, pawpaws, peaches and pomegranates was established; as there were no restrictions on anyone helping themselves it soon became popular, especially among the children on their way to and from school who would pluck lemons and suck them with great relish. | ||

Next it was decided to provide overnight accommodation for members who traveled long distances for Akhand Paaths and who had no relatives or friends in Nakuru with whom they could stay. Rest-house accommodations were built comprising rooms, a kitchen and communal bathroom. Sardar Kishen Singh, the railway shed master in Nakuru, devoted a great deal of time and hard work to this development. In later years the accommodation became popular with foreign backpacking tourists who could not afford expensive hotel accommodation. | Next it was decided to provide overnight accommodation for members who traveled long distances for Akhand Paaths and who had no relatives or friends in Nakuru with whom they could stay. Rest-house accommodations were built comprising rooms, a kitchen and communal bathroom. Sardar Kishen Singh, the railway shed master in Nakuru, devoted a great deal of time and hard work to this development. In later years the accommodation became popular with foreign backpacking tourists who could not afford expensive hotel accommodation. | ||

In the early days some settlers, who were familiar with Sikh traditions from the time of the British 'Raj" in India, transported their Sikh employees to celebrate their ‘Jor Melas' (a form of celebration) and stayed on to join the 'Langar' (Community meal) after finishing their business in town. The settlers did not escape the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s. Many Sikhs, working on the farms, lost their jobs, for them the Temple rest-house was a boon. A few even camped around the precincts, and showed resilience by planting cabbages, peas, potatoes, beans and maize. S. Pritam Singh Ahluwalia, who had a grain mill at Rongai and was a generous man, regularly supplied wheat floor to the temple although he was himself affected by the depression. | In the early days some settlers, who were familiar with Sikh traditions from the time of the British 'Raj" in India, transported their Sikh employees to celebrate their ‘Jor Melas' (a form of celebration) and stayed on to join the 'Langar' (Community meal) after finishing their business in town. The settlers did not escape the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s. Many Sikhs, working on the farms, lost their jobs, for them the Temple rest-house was a boon. A few even camped around the precincts, and showed resilience by planting cabbages, peas, potatoes, beans and maize. S. Pritam Singh Ahluwalia, who had a grain mill at Rongai and was a generous man, regularly supplied wheat floor to the temple although he was himself affected by the depression. | ||

A few of the affected Sikhs opted to return to their villages in India while some decided to stay on. Sardar Inder Singh of Revelco developed a system of rotational employment in his contracting business so that those employed could save enough to travel to India. It was a simple system and it worked: men would be employed for a month and make way for another lot and so on. The idea caught on and employers in Nairobi followed the example and allowed many of those who had lost their jobs through no fault of their own, to earn enough for the fare by ship to India. | A few of the affected Sikhs opted to return to their villages in India while some decided to stay on. Sardar Inder Singh of Revelco developed a system of rotational employment in his contracting business so that those employed could save enough to travel to India. It was a simple system and it worked: men would be employed for a month and make way for another lot and so on. The idea caught on and employers in Nairobi followed the example and allowed many of those who had lost their jobs through no fault of their own, to earn enough for the fare by ship to India. | ||

[[Image:STN2.jpg|thumb|200px| | |||

[[Image:STN2.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Burned Ruins of Sikh Temple Nakuru in 1936]] | |||

In 1936 disaster struck: the Temple was gutted by fire and reduced to ashes. Although the cause of the fire was a source of speculation, it was probably accidental. A lantern was always left burning throughout the night and it is likely that it was tipped over and set fire to the furnishings. Whether it was tipped over by thieves or a cat will never be known. The Sikh community tackled the disaster with typical courage and fortitude; part of the rest-houses were modified and decorated to house the Guru Granth Sahib and used as a temporary Temple. | In 1936 disaster struck: the Temple was gutted by fire and reduced to ashes. Although the cause of the fire was a source of speculation, it was probably accidental. A lantern was always left burning throughout the night and it is likely that it was tipped over and set fire to the furnishings. Whether it was tipped over by thieves or a cat will never be known. The Sikh community tackled the disaster with typical courage and fortitude; part of the rest-houses were modified and decorated to house the Guru Granth Sahib and used as a temporary Temple. | ||

---- | |||

Article adapted from Sikh Temple Nakuru - Vaisakhi 1999 Souvenir Book. | |||

Souvenir Text Complied by Sardar Pyara Singh MBE with notable assistance of Sardar Patwant Singh, Nottingham U.K.and Sardar Didar Singh Bhangu, a long serving member of the Community. | |||

---- | |||

Revision as of 21:10, 7 December 2008

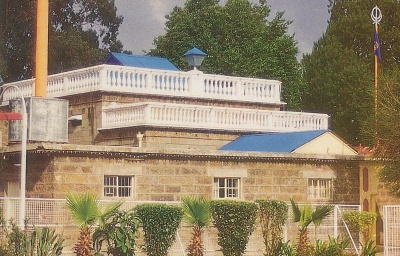

Sikh Temple Nakuru, A Brief History

The history of Sikhs in Kenya’s Rift Valley and its largest town, Nakuru, is long and distinguished. In the early years many worked for the railway, the biggest employer, while others were employed by the Government Public Works Department and by the many European farmers who had settled in the areas towns – notably Elburgon, Gilgil, Londiani, Mau, Narok, Molo Naivasha, Thompson’s Falls and Subukia.

When people migrate from one geographical region to another they generally carry with them their cultural and religious values and beliefs. The Nakuru Sikhs were no exception and the fact was recognized in 1903 by the railway authorities who allocated a plot, north of the Nakuru marshalling yards, for the construction of a Gurdwara. As in other cases, most of the early Gurdwara’s in Kenya were built along the route of the railway.

The first Nakuru Gurdwara soon became a center for regular diwans (assemblies) and for celebrating Gurpurabs (a festive, special occasion) attended by Sikhs from all over the Rift Valley. Many of the European settlers employed Sikhs from all over the Rift Valley. Many of the European settlers employed Sikhs on their farms and held them in high esteem as hard working people with an all-around ability to tackle any job. Most of the Sikhs had technical backgrounds, and were skilled in sawmilling, mechanical engineering, construction, cabinet and furniture making and were also able to thrive under harsh conditions. Lord Delamere, who farmed vast tracts of land around Njoro and Elementetia, employed a number of Sikhs as syces (grooms) and jockeys for his horses which he raced in Nairobi at the old racecourse (which is now known as Racecourse Road in Nairobi City).

Earlier records indicate that the present plot was acquired on 1st April 1917 and the title registered on 3rd June 1918 in the name of S. Gian Singh, S. Boota Singh, S Wariyam Singh, S. Santa Singh and S. Dausanda Singh as trustees.

As the community grew the need for another larger plot was recognized. In 1925, Sardar Sunder Singh was deputed to be the community’s spokesman to the administrative authorities in negotiations for another larger plot. Sunder Singh was an overseer on Keringet Estate in Molo with a number of Sikh artisans working under him. He spoke English well, fairly uncommon in those days, and a good communicator and the ideal candidate to present the communities case. A plot, where today’s temple stands, was quickly allocated but the grant brought the Sikh community into dispute with the neighbors. However, with the assistance of the then District Commissioner, Mr. Hobley and the indulgence of Sardar Sunder Singh, the matter was promptly resolved to allow the Sikhs to go ahead with developing their temple plot.

The community stalwarts wasted no time and in about 1926-27 a fully functional and decorated building was completed in three months. The Gurdwara was built with timber framework, clad with corrugated sheets and lined with tounge-and-groove timber and with verandahs on the north, south and west sides and painted throughout.

The new Gurdwara became the central place of worship and was well attended for every Sikh religious function and celebration. As the area developed agriculturally and commercially the membership increased. The plot was fenced with cedar posts and steel wire interleaved with bamboo splits, or ‘droppers’ and the surrounding grounds were improved. An orchard of lemons, guavas, pawpaws, peaches and pomegranates was established; as there were no restrictions on anyone helping themselves it soon became popular, especially among the children on their way to and from school who would pluck lemons and suck them with great relish.

Next it was decided to provide overnight accommodation for members who traveled long distances for Akhand Paaths and who had no relatives or friends in Nakuru with whom they could stay. Rest-house accommodations were built comprising rooms, a kitchen and communal bathroom. Sardar Kishen Singh, the railway shed master in Nakuru, devoted a great deal of time and hard work to this development. In later years the accommodation became popular with foreign backpacking tourists who could not afford expensive hotel accommodation.

In the early days some settlers, who were familiar with Sikh traditions from the time of the British 'Raj" in India, transported their Sikh employees to celebrate their ‘Jor Melas' (a form of celebration) and stayed on to join the 'Langar' (Community meal) after finishing their business in town. The settlers did not escape the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s. Many Sikhs, working on the farms, lost their jobs, for them the Temple rest-house was a boon. A few even camped around the precincts, and showed resilience by planting cabbages, peas, potatoes, beans and maize. S. Pritam Singh Ahluwalia, who had a grain mill at Rongai and was a generous man, regularly supplied wheat floor to the temple although he was himself affected by the depression.

A few of the affected Sikhs opted to return to their villages in India while some decided to stay on. Sardar Inder Singh of Revelco developed a system of rotational employment in his contracting business so that those employed could save enough to travel to India. It was a simple system and it worked: men would be employed for a month and make way for another lot and so on. The idea caught on and employers in Nairobi followed the example and allowed many of those who had lost their jobs through no fault of their own, to earn enough for the fare by ship to India.

In 1936 disaster struck: the Temple was gutted by fire and reduced to ashes. Although the cause of the fire was a source of speculation, it was probably accidental. A lantern was always left burning throughout the night and it is likely that it was tipped over and set fire to the furnishings. Whether it was tipped over by thieves or a cat will never be known. The Sikh community tackled the disaster with typical courage and fortitude; part of the rest-houses were modified and decorated to house the Guru Granth Sahib and used as a temporary Temple.

Article adapted from Sikh Temple Nakuru - Vaisakhi 1999 Souvenir Book. Souvenir Text Complied by Sardar Pyara Singh MBE with notable assistance of Sardar Patwant Singh, Nottingham U.K.and Sardar Didar Singh Bhangu, a long serving member of the Community.

Sikh Temple Nakuru is now pin pointed to its exact location on the Gurdwara's Map application. Check it out here - Gurdwaras East Africa

Click on the photo to see them enlarged