Bhagat Puran Singh

'Samaritan of Amritsar' by Khushwant Singh

Any visitor to the city of Amritsar who keeps his eyes open, cannot fail to notice black wooden boxes, bearing crude writings in white in Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu and English, placed in crossings and public thoroughfares, reminding him of the duty he owes to his brethren, the sick and suffering, the aged and the infirm. At some places he may come across large wooden black-boards bearing extensive writings of a similar type seeking to strike a sympathetic chord in him or containing a homily on civics and morality, religion and philosophy. If he were to pause and read, he would surely find that these are the insignia of Pingalwara (literally a home of the cripple)-a unique institution founded by an equally unique person.

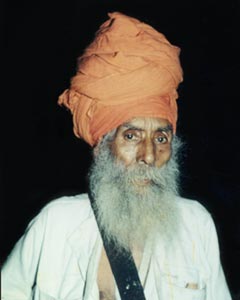

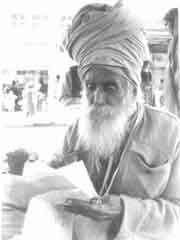

He is a tall, shabbily dressed man, who may be found tramping with his wooden sandals or riding a rickshaw, along with an invalid. He always carries a brass bell hanging by his side and announcing his rrival. This man, you may call him a superman, even an angel, goes by the name of Bhagat Puran Singh. He was born and brought up in a Hindu family of village Rajewal (Rahnon) in Ludhiana district but he found greater solace and inspiration in the teachings of the Sikh Gurus, when, in spite of his intense passion for learning, poverty forced him to discontinue his studies in the tenth class of a high school. So he adapted his erstwhile worldly dreams, for their fulfillment, to a nobler atmosphere of spirit that the Gurdwara Dehra Sahib of Guru Arjan Dev and Shahid Ganj of Bhai Mani Singh, the princes among the martyrs, provided him at Lahore. He, therefore, lost no time in taking a vow of celibacy dedicating his life to the service of suffering humanity. He started at Lahore his career of social and humanitarian activities.

This was in the year 1924 when Puran Singh was hardly a youth of 19. Since then he has been indefatigably carrying on his altruistic activities, day and night in scorching heat and biting cold, in rains and under dust storms, undeterred by adversities, undaunted by criticism, and unruffled by the obstacles that crop up on the path of social service. His enthusiasm knows no bounds and his determination remains unshaken. Friend of the forlorn, helper of the helpless, a ready nurse for a patient of any disease however loathsome, infectious, unmindful of his personal health; safety or convenience, making not the slightest distinction on the basis of caste, creed or community regarding the person in need of his service; this single man has, by his example and precept, inspired many and with their co-operation has, in a short space of nine years, built from a scratch what may justly claim to be an institution.

You may not know Bhagat Ji, but if he were to come to sense you as a man who can assist him in furtherance of his noble cause, even to a small extent, he is sure to find you out, and may even urge you to help and contribute to his cause. To the writer he became known in about the year 1940 when he walked barefooted and half naked on the roads of Lahore, usually with a cripple boy as his sacred load on his back and picking up all things like the stone, metal pieces, banana peels, nails, horse-shoes and brick bats that my interfere with the convenience and safety of vehicles and public. His humanitarian activities justified the renewal of his acquaintance and casual visits of the writer to the place of his activities.

Though unable to have academic education within the four walls of a regular educational institution, Bhagat Puran Singh, on account of his inborn zeal, has by constant personal effort, acquired a vast amount of knowledge on various topics and in the words of Principal TejaSingh "has reached the highest level of thought through practically associating himself with the realities of life". This passion of learning he manifested very early and is associated with an equally great enthusiasm to spread light of knowledge among others. He has, therefore, accumulated a large collection of books and old copies of several journals. The number of books and journals is evidently sufficient for running a small library and a reading room.

In the main ward is housed another section of the publications, and printing press which has to its credit not less than sixty books, booklets, pamphlets, posters and placards. Looking at the wide range of the subject of his publication, it can be said without exaggeration that his printing department is verily a transmitting station of valuable information for the guidance and reconstruction of man and society.

Original in its concept, the institution represent a natural outcome of an irresistible urge of Bhagatji to do his best for the poor and helpless patients, who cannot gain admission into the hospitals. Such an idea could, as a matter of fact, take its birth in the mind of a poor man only and not a rich man, because the approach of each, to such a social problem, is radically different. A rich person always thinks in terms of endowing money and running his Own independent hospital, self contained in every respect. He thinks of providing his own doctors, his own equipment with medical or surgical apparatus, an aspect of the hospital, which is very costly as it eats a lion's share of the hospital's maintenance funds. This is all very well in a place, where there is no hospital. But in a central city like Amritsar, where a highly equipped hospital exists, what is needed by the common man, is not another equally self contained hospital, but greater boarding facilities, so that he may be able to avail himself of the outdoor treatment provided by the central (standard) hospital. The question of opening another hospital at one place arises only when the existing facilities for outdoor treatment are exhausted, since extension of outdoor facilities in a well-equipped hospital costs only a fraction of the outlay necessary for an additional hospital. This, according to Bhagatji, is the raison-de-etre of Pingalwara and a suggestion for the consideration of rich persons, interested in founding hospitals for public good.

Another contention of Bhagatji is that howsoever rich a man may be and howsoever great his endowment, in the matter of establishing or running a hospital, he cannot compete with or equal the collective effort of society. Puran Singh's resourcelessness had led him to the finding of a solution that has surpassed that of the wealthiest man with his big endowment. In his resourcelessness he could not think of any big endowment of money but the aforesaid two ideas, which are greater than big endowments.

The problem of sickness in our country is awfully large. The helpless and the homeless patient dying on the roadside is a very common sight with us. In the city of Amritsar, by no means wealthier than other cities of India, rather smaller in size than many of them, not even the seat of government, the problem of the helpless patients continued to persist for a long time before the partition of the country. Though very rich and noted for their philanthropy, the people of this city could not dream of the miserable plight of such persons as are now looked after in the Pingalwara. With our people, so poor is the notion of human dignity that the spectacle of a helpless patient dying on the road-side, unattended and uncared for, is taken as the inevitable fate of a human being.

As a man of deep religious feelings and convictions Bhagat Puran Singh has solved this question by invoking and canalising the religious sentiments field hitherto neglected even by notable men of all religions. He has thus thrown a challenge to the religious people, to take up earnestly this great neglected cause. This negligence goes to mar the dignity of man and degrades our nation in the eyes of other advanced people. Here is a call not only to the normal ritual, charity to divert its flow but also to the daily charity in petty sums of an anna or two. (five paise coin or ten paise coin).

Shree Acharya Vinoba Bhave said the other day that the Indian temples played a very significant part in the social and cultural life of India. This Pingalwara is a temple of God without any idol or a representative religious symbol of God installed in it. The only symbol of God in the Pingalwara is the destitute bodily helpless man. The aim and chief function of the Pingalwara is the care of the physically helpless people, whether in the grip of infirmity or old age or afflicted with sickness. But in view of its educational activity, the institution is also a social laboratory wherein the solution of many a social problem is not only discovered but from where it is also broadcast with an effective and original method of publicity. As such, this kind of temple represents a great effort of intelligent humanitarianism and is destined to play its own role in the cultural history of the country.

It is unfortunate that the word Pingalwara coined by Bhagat Ji, does not fully convey the scope of its various activities and, for some people, creates a queer impression, such as that of a leper asylum' but the word is gaining a household currency in Northern India. The appalling shortage of beds in the hospitals is resulting in pushing a constantly increasing number of patients to the Pingalwara which in Northern India, is now shouldering a central burden and as such is entitled to obtain help from all persons in the region. However, further to enlist the sympathy of the public a good deal of publicity work has to be done in the territory. For this, more funds are required since the income, though apparently large, is not keeping pace even with basic expense of Pingalwara and the inevitable gap not only keeps the standard of service in the institution too low but also leaves little margin for further developmental work, including publicity, for which Bhagat Ji has to make special efforts to secure funds from persons interested in this sort of work.

Puran Singh's Pingalwara is truly a nucleus of a great humanitarian movement. In the words of Principal Teja Singh it is "an island of Gandhism in the midst of clamorous politics and show."

'Humility is my mace' by V.N.Narayan

He looks like the rishies of old and the Khalsa of Guru Gobind Singh—a veritable combination of courage and compassion, a total embodiment of unselfishness and service. Bhagat Puran Singh is what India’s distilled wisdom and rich heritage are all about.

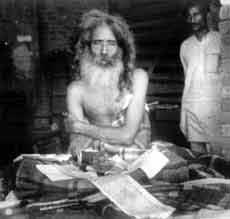

There he sits, at the entrance of the Golden Temple at Amritsar, with loads and loads of paper around him. In front of him is a brass vessel as nondescript as the man’s physical appearance. Visiting devotees to the shrine stop, pay silent obeisance, put some cash into the tray and move on. Bhagat Puran Singh neither seeks nor acknowledges their greetings.The money piles up, but the sage notes it not, and along comes a seeker and the sage welcomes with open arms.

There is spontaneous rapport and the generation gap is closed. You wonder what this wizened old man has - anything at all - to say and minutes later there is another kind of wonder : how is it that this frail man of near ninety is so well versed in ecology, environment problems, the Tehri dam, Narmada and deficit financing. The words of Guru Nanak in Var Asa flash through the mind

"He who attains humility through love and devotion to God, Such a one may attain emancipation".

If you are from the Tribune ? I have reprinted your article on ... (he turns to one of the Sewadars to open a bundle). The Times of India had a series of articles on this subject..."

Amazing that he should tell a journalist what the journalist had written. Perhaps the transience of journalism acquires the trappings of immortality through not a mass medium but a spiritual one. Bhagatji subscribes to two dozen regional, nation and international dailies and magazines - and reads them all.

What obsesses us most - the daily obscenities of politician and editorial homilies of journalists—does not occupy his attention for more than a fleeting moment. Bhagatji, over the decades, has developed a feel for real news, that which concerns the people, society at large and the values that (ought to) govern it.

He is gentle, soft and sublimely uncritical of anything around him. To him, all of God’s creations are sacred, be the animal, vegetable or mineral or whatever. He collects, as he walk along the streets of Amritsar, pebbles, horse-shoes, peculiar shaped stones, and a lot else...

An important, looking SGPC functionary, surrounded by kirpan-wielding assistants and armed guards, passes by. Somehow, the presence of Bhagat Puran Singh with no guards, no security, no Paraphernalia, seems irksome and out of place. What is the secret of this man’s impregnable security ? Guru Arjun Dev has the answer :

"Humility is my mace;

Touching The dust on the feet of the people, my spear

These weapons no-evildoer can withstand,

The Master, all-endowed, has armed me with these",

(Sorath 80)

The picking of pebbles on the street is very symbolic. After all for, close to seven decades Bhagatji had been picking up human pebbles cast away on the street by a cruel destiny or an uncaring society. God helps those who help themselves; Bhagat Puran Singh has vowed to help those who can’t help themselves.

He is the saint of our times. Contemporary history has few names ( I have Mother Teresa in my mind when I write this) which can boast of such relentless service to humanity as that of Bhagat Puran Singh. "Binu seva phal kabhu na pawasi seva kami sari". Talking to him is enlightening. He has very simple remedies for almost all the nation’s ills. All perfectly practical and easily enforceable - but in a nation of Bhagat Puran Singh.

A few public spirited Indians in the USA have started a movement to recommend the Noble Peace Prize for Bhagatjl. He would be the last person to be enthusiastic about it. He knows the difference between the emancipated soul and the good Samaritan, the difference that would explain why Martin Luther King’s non violence struggle was worthy of Nobel Award, and why the Noble Prize is unworthy of Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagriha and Ahimsa.

But the prize money - around Rs. 40 Lakh - is welcome if only to house Pingalwara in a better building and with improved hygiene and amenities. Also, the Noble Prize needs to redeem its honour by going to the right persons. The cause must be taken up by the country at large.

Meanwhile, the saint goes on unworried by the mess caused by our leaders to the country. Bhagat Puran Singh would echo Guru Nanak Dev...

"I have learnt by the light shed by the

Master, perfectly endowed;

Recluse, hero, celibate or sanyassi -

No one may expect to earn merit

without dedicated service—

Service which is the essence of purity."

V.N. Narayanan

Editor-in-Chief, The Tribune Chandigarh

'Remembering a Sage' by V.N.Narayan

On an August day falls the death anniversary of Bhagat Puran Singh, the sage of Pingalwara (Amritsar). The last few weeks of this servant of the hapless and the forlorn were full of pain, which reminded one of the suffering of Christ on the Cross. The day after his passing into eternity was the sixth day of August. Pasternak says in "Zhivago's Poems": "You walked in a loose crowd. /Then someone remembered/ That by the Old Calendar/Today was the sixth of August, /the Lord's Transfiguration." Was it a coincidence or a manifestation of the Supreme Will? This great man is not dead. He lives on amidst the suffering people, transfigured and immortalised. He did not work miracles. But he did reveal, in word and deed, the power to transform lives, alleviate pain and lift up such hearts as are hurt, depressed and disconsolate.

We remember him respectfully because he was different from most of us: he worked recklessly but splendidly to show us how not to make yesterday's cup of bitterness "more full with the pain of today." He sought to shake society out of its sloth, not with aimless fury but with deliberate effort, and found for grief the panacea of service humility and compassion. He had immersed himself in the teachings of the Gurus. He had imbibed the essential Gandhi as he had assimilated history and the distilled wisdom of the centuries. There was no fretting or regretting.

His was a life well-lived. Ours are lives spent in the settling of scores and in the settlement of accounts. He was a Bhagat (a devotee), Puran (whole) and Singh (a lion). Few names suit a person so aptly. The lion-hearted devotee wanted us to realise what the Rishis have commanded us to be: Be thou whole. The rest is immaterial. "People are my God," he said. He worked for their well-being. Nothing else mattered. Nothing else matters for an unfragmented person like him. He did things in great sweeps. He had the choice of working in certain spheres which promised comfort, money and material satisfaction. He chose a path which brought him, all these "gains", but not for himself. What personal consideration would-matter to a man who had learnt to remember this; "Truth is our another, justice our father, pity our wife, respect for others our friend and clemency our children; surrounded by such relatives, we have nothing to fear"?

The curvilinear movement of life took him from his place of birth in a well-to-do Hindu family of Ludhiana, through hard times and with little formal education, to Gurdwara Dehra Sahib in Lahore. His mother had prepared him for the daunting tasks ahead. A crippled and mentally retarded child, spotted by him near the gurdwara, confirmed him in his mission. As Jesus founded his church on Peter, his rock, Bhagat Puran Singh laid the foundation of his Pingalwara on the ennobling presence of this beloved child named Piara Singh. Lahore's Dyal Singh Library helped him in self-education. The inhuman condition thrown up by the country's partition led him to the ideas of organised and institutionalised patient-care.

All forms of handicap could be treated and mitigated, he said. No stigma was irredeemable, he taught. Hundreds of unbearable lives were made worth living by him. Women and children were the main beneficiaries of his "God-guided" plans. He inculcated in people the habit of giving until it hurt. Pingalwara became a metaphor of help in a world full of misery. The institution has grown and become the centre of a service movement. Will it remain so? No one knows the answer. His death could not destroy Bhagat Puran Singh. The deterioration of his institution can do so. Our duty to the Pingalwara (s) is clear. The sage told us that abandoning the instinctive pursuit of self-interest, man must cultivate the higher instincts of sympathy and mutual help. We felt supremely happy by achieving the political miracle of freedom on the quicksand of social slavery and inner corruption. This teacher of ours warned us against viewing historical surprises as the roots of our troubles. The strength of the many must conquer the sufferings of the few. Finite man has infinite capabilities; realise this; work; suffer; mitigate suffering ... Bhagat Puran Singh's thoughts should form part of the process of our daily examination of conscience.

'Bhagat Puran Singh's Writings & Love For Literature' by Principal Teja Singh

The period of Bhagat Puran Singh's relationship with me is hardly three years. During this period he has been seeing me off and on in connection with his literary activities. In the course of this period I have found him to be inspired with an unusual zeal for social and literary work.

His eagerness has always so switched my intellectual reserves that whenever he has sat by my side I have invariably been invoked to pour out my whole knowledge on any topic of the moment. His presence has always afforded me a relief by giving me an opportunity to give an outlet to my thought which buried deep in memories.

During my whole life including the 40 years of my educational career I have found him to be the only man who has sat by my side as an earnest and most zealous student of literature.

He is an example of a man reaching the highest level of thought through practically associating himself with the realities of life as apart from mere bookish study gleaning borrowed truths which always carry with them musty stench of aged. His truths are discovered not from books, but from active throbbing life. He is an example of learning by experience in the best Indian traditions of Malabari (Parsi) Bhai Pheru and Nawab Kapur Singh. He has revived those Sikh legends which had become almost unbelievable. In this respect his example will serve as a beacon light for all aspirants emerging from low stations of life.

He has created a new front, that of healthy literature, that provokes new thoughts, stirs up new emotions, gives new urges for active good, He has launched a new campaign of social welfare through publicity the beginnings of which are developing into great heights.

His work in the cause of the submerged humanity-the aged, the infirm, and the sick is not only monumental but original'-in conception destined to go down in the annals of the social history of India.