Tagore and Sikhi

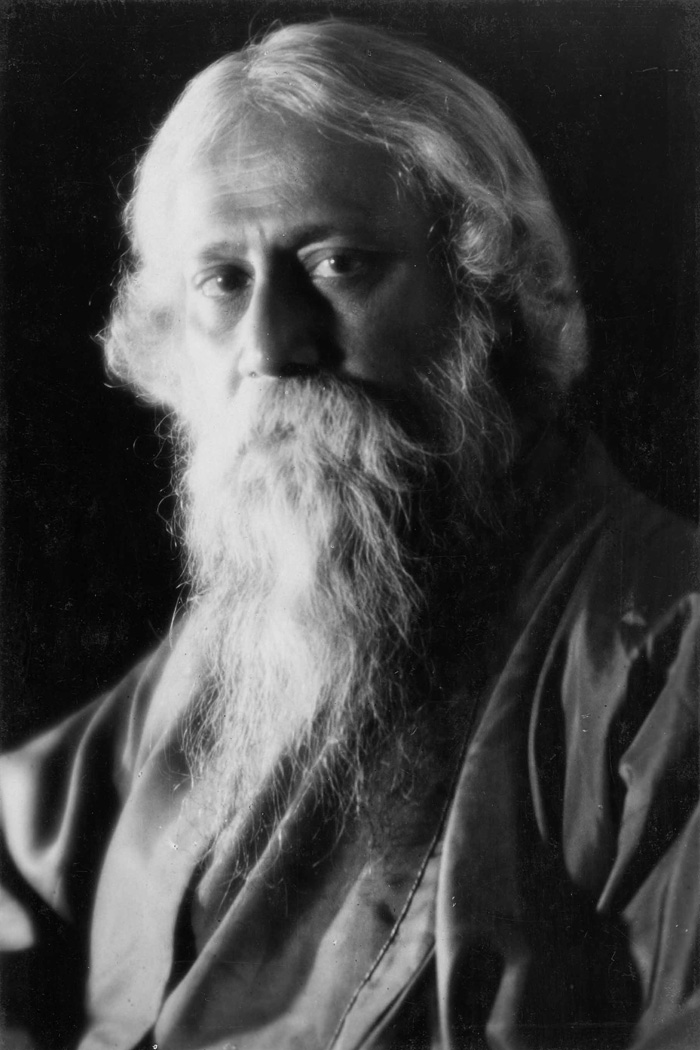

Rabindranath, the youngest son of Maharshi Debendranath Tagore was born in Jorasanko on 25th Baisakh, 7th May 1861.Died on 7 August 1941 (aged 80) Rabindranath’s grandfather Prince Dwarkanath Tagore. As the thirteenth child in a wealthy, Bengali brahmin family that was devoutly Hindu yet also strongly political His father and grandfather were deeply involved with an emerging religious movement called the Brahmo Samaj Tagore was against the rituals and practices of Hinduism.

Rabindranath Tagore, Kashmir and the Sikhs

by Jasbir Singh Sarna

Source:-Sikhnet It is interesting to note that Tagore had always been deeply influenced by the philosophy and history of Sikh religion. In 1885 Tagore wrote an essay 'Beer Guru' (valiant saint) which was his veneration of Guru Gobind Singh. Tagore wrote three poems on Guru Gobind Singh viz Nishfal-Hpahaar, (1888, Futile Gift), Guru Gobinda (1899) and Shesh Shiksha (1899, last teachings).

In his another poem 'Prarthonate Daan', the inspiring story of Bhai Taru Singh is mentioned who was executed by the Mughal Governor. In his yet another all-time classic poem 'Bondi Bir' he eulogizes Sikh valor and pays a poetic tribute to "Baba Banda Singh Bahadur", the military commander of Guru Gobind Singh. The famous Punjabi artist Sir Sobha Singh (1901-1886) and renowned folk song compiler Devendra Satyarthi were also deeply influenced by Tagore and adopted Tagore's ideals and even his looks.

Rabindra Nath Tagore was always an inspiration for Punjabi intellectuals, to boost their mother tongue Punjabi. He inspired Dr Allama Iqbal and the actor Balraj Sahni including many others to love their mother tongue. In one meeting he told harshly to Balraj Sahni, "Hindi is not your mother tongue you are Punjabi. Why are you not writing in Punjabi language I am writing in Bengali, which is regional language. In spite of that, not only India but the whole world reads my writings.

The question is not of excellence but a writer should be deeply associated with his birthplace, people and language. I do not agree with you that Punjabi is a remote and low language. The language in which Guru Nanak Dev Ji like famous poets wrote poetry is excellent one. Punjabi and Bengali literature are very old. I am trying to translate some verses of of Guru Nanak Dev Ji into Bengali but I am sure I will not do justice. In these circumstances you spend whole of life writing in other languages...".

Tagore came to Kashmir in 1915 on the invitation of his close friend and Bengali poet Jagdish Chander Chatterjee, who was the superintendent in Kashmirs Government's Research Department. Tagore along with his son and daughter-in-law and one Bengali poet Satindernath Datta came to Kashmir via Rawalpindi. Chatterjee hired a beautiful houseboat 'Paristan' for Tagore and his fellows. They visited a number of places in Kashmir. He felt proud to meet farmers, artists and craftsmen. In Srinagar, a poetic symposium was conducted in Sri Pratap College where poets, intellectuals and artists gathered together. Tagore came to the dais and with beautiful words mentioned the natural sceneries, historic background and Kashmir's cultural aspects.

A small poetic symposium was also held in the house of Pandit Anand Koul Bamzai, on the right bank of Jhelum (Habba Kadal). Tagore praised the poets like poet Mehjoor and Zinda Koul. Kashmiri literary figures met Tagore in a houseboat and offered gifts to him. The golden shining moon, the dawn, the bright sun rays, cold night, all inspired him. He wrote some poems in Kashmir. The beautiful mountains, forests, sweet springs and natural brooks of Kashmir are absorbed in his writings. Kashmiris along with other Indians celebrated his birthday in 1961-62 in Srinagar. The Government of Jammu & Kashmir established 'Tagore Memorial Hall' in his memory. This hall continues to be a vibrant hub of cultural, literary and intellectual activities till date.

RABINDRANATH TAGORE'S PERCEPTION OF THE SIKHS IN HISTORY

by Ranjit Sen

Source:-JSTOR

His Quote for the Book:-Today there is no spirit of progress among Sikhs. They have crystallized into a small sect.

-Journal Information The annual journal of the Indian History Congress, entitled The Proceedings of the Indian History Congress carries research papers selected out of papers presented at its annual sessions on all aspects and periods of Indian History from pre-history to contemporary times as well as the history of countries other than India. The addresses of the General President and the Presidents of the six sections generally take up broad issues of interpretation and historical debate. The journal has constantly taken the view that ‘India’ for its purpose is the country with its Pre-Partition boundaries, while treats Contemporary History as the history of Indian Union after 1947. The papers included in the Proceedings can be held to represent fairly well the current trends of historical research in India. Thus there has been a growth of papers on women’s history, environmental and regional history. This journal has appeared annually since 1935 except for five different years when the annual sessions of the Indian History Congress could not be held.

-Publisher Information The Indian History Congress is the major national organisation of Indian historians, and has occupied this position since its founding session under the name of Modern History Congress, held at Poona in 1935. In his address the organisation's first President, Professor Shafaat Ahmad Khan called upon Indian historians to study all aspects of history, rather than only political history and to emphasize the integrative factors in the past. Its name was then changed to Indian History Congress's from its second session held in 1938, and three section, 1. Ancient, 2. Medieval and 3. Modern were created for simultaneous discussions. Ever since 1938 the organisation has been able regularly to hold its sessions each year, except for certain years of exceptional national crises. It is now going to hold its 77th annual session at Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, on 28-30 December 2016. It has at present over 7,000 ordinary and life members.

Tagore and Sikhism

by Amiya Dev

Source:-Mainstreamweekly

Rabindranath Tagore wrote six poems on Sikh heroism and martyrdom, two in 1888, three in 1898, and one in 1935. Of them three are on Guru Gobind Singh, one on Banda Bahadur, one on Bhai Torusingh, and one on the boy, Nehal Singh.

The Guru Gobind Singh poems are spaced between his twenty year-long sâdhanâ to be worthy of his leadership, and his death, the height of the sâdhanâ being his refusal to a rich gift brought by a disciple (the theme so enthralled Tagore that he wrote the same poem twice and on the same day), and the death being self sought in expiation for a thoughtless killing.

The Banda Bahadur and Nehal Singh poems are built around the Mughal siege and eventual fall of the Gurudaspur fort and the subsequent carnage and martyrdom, especially of the two of them, Banda being forced to kill his own son and Nehal Singh defying his mother’s plea that he wasn’t Sikh.

Martyrdom is also the theme of the Torusingh poem, he offering his head with his braid which his captor had asked him to cut off.

The poems were preceded in 1885 by three essays addressed to the juvenile readers of the Jorasanko house—one on Guru Nanak’s life in the background of his father’s money-mindedness; a second one on the heroic Guru Gobind Singh ever fighting for Sikh indepen-dence; and a final one on that independence as attained and bloodily guarded by Banda Bahadur and others until the advent of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Tagore had visited Amritsar at the age of eleven in 1873 with his father, Debendranath, on their way to the Himalayas. The latter had come to Amritsar before, his interest in Sikh monotheism as propounded by Guru Nanak much influencing his Brahmo faith. In Tagore’s autobiography, My Reminiscences (1912), he recalls his sense of wonder as a boy at the Golden Temple:

“I remember the Gurudarbar at Amritsar like a dream. Many days with father I walked to that Sikh temple in the middle of a lake. Prayers were being said there all the time. My father would sit among those Sikh worshippers and at some point join in the singing; on hearing their songs of devotion from an outsider they would be much inspired and respect him. ... Once he had a singer from the Gurudarbar come to our house and sing bhajans for him.”

On his earlier trip in 1857 Debendranath had collected the famous Nanak bani ‘gagan mai thâlu ravi-candu dÑpak bane...’,translated it into Bengali, had that translation printed, and either he himself or had his son Jyotirindranath set it to music. Young Rabi must have sung it at Brahmo festivals. The âratÑ motif of this song (‘kaisÑ âratÑ hai/bhavakhandanâ terÑ âratÑ’) may remind us of a song Tagore wrote a few years later, in 1884: ‘Tânhâre ârati kare candra tapan ...’ (Him the moon and sun offer ârati ...), a song Vivekananda was fond of.

Similarly, his other devotional songs of the mid-eighties may not be very far from the spirit of Nanak-bani—for instance, ‘e parabâse rabe ke hây ...’ (How go on with this sojourn here ...: 1885) and ‘andhajane deho âlo, mritajane deho prân ...’ (Give light to the blind, give life to the dead ...: 1886).

Later, in 1909, he came across a pleasant Sikh bhajan—‘bâdoi bâdoi ramyabÑnâ bâdoi ...’—which he translated into Bengali (‘bâje bâje ramyabÑnâ bâje ...’ [The lovely binâ breaks into music ...] and developed into a regular song with two additional stanzas (‘nâce nâce ramyatâle nâce ...’ [Dances in a lovely beat ...] and ‘sâje sâje ramyabeœe sâje ...’ [Dresses in lovely attire ...].

Another Sikh bhajan he translated and published in 1914 was: ‘e Hari sundar e Hari sundar ...’, the translation being close to the original, with no change in the first line, for instance.

1909 to 1914, in fact somewhat earlier than 1909 to somewhat later than 1914, was a period in Tagore’s career as a poet-composer when the spirit of Nanak, and Kabir, and a number of other Sants from medieval India seemed to have fit into his creative psyche. We recall that in 1914 he brought out, with assistance from Evelyn Underhill, One Hundred Poems of Kabir. Notwithstanding the scholarly doubt about the full authenticity of his Kabir sources, his regard for Kabir was unbounded. But some of his Western admirers’ putting Kabir and him on the same scale and preferring Kabir to him was misjudgement, for Kabir was primarily a Sant whose poetry, oral, was only an effective medium. Tagore, on the other hand, was primarily a poet and composer (Sant Tagore would indeed be a travesty), fully conscious of his craft, experiencing a degree of devotion in the period we are talking of. Obviously the same distinction applies to Guru Nanak and Tagore, Sant and poet. (Perhaps we would understand this distinction better if we place Tagore beside someone nearer home—Rama-krishna Paramahamsa whose words were as full of faith as wisdom and who by all means was a saint.)

To Tagore Kabir and Nanak were true propagators of what he meant by dharma; and what he meant by dharma would perhaps be clear from the following excerpts from his essay, ‘The Simple Ideal of Dharma’ (1903):

“If I have to light a lamp at home, I have to make much effort ... I have to keep track of where mustard is sown, where oil is pressed from it, whereabouts of the oil market, and then there is all the going about dressing up an oil lamp—after such elaborations what meagre light do I get? My immediate purpose may be served, but it only doubles the darkness outside.

“To get the world-revealing morning light I don’t have to depend on anyone—don’t have to manufacture it; all I have to do is wake up. As I open my eyes and unbar my door that light floods in which no one can stop. ...

“As this great light is, so is dharma. It too is immense, it too is simple. It is God gifting Himself—it is timeless, it is boundless; ... To have it, we only need to ask for it, to open our hearts.”

It is in this perspective that we may look up his essay on ‘Shivaji and Guru Gobind Singh’ written in 1910 as preface to Sarat Kumar Roy’s book, Sikh Guru o Sikh Jâti. While Maratha history under Shivaji was political (and a history that eventually failed), Sikh history at the outset was religious.

‘The freedom that Baba Nanak had felt was not political freedom; his sense of dharma was not constricted by the worship of deities that was limited to a certain land’s or people’s imagination and habit, and did not accommodate the universal human heart, on the contrary restrained it; his heart was free from the bonds of these narrow mythological religions and he dedicated his life to preaching that freedom to all.’

‘But come to be oppressed by the Mughals the disciples (œishya>Œikh) of Nanak turned into a community of their own, and for that reason their prime effort became defending themselves from harassment and surviving, rather than preaching religion all around. ... Their last Guru was especially devoted to this task.’

This was the thrust of Tagore’s argument. He summed it up in the following words:

‘Nanak gave a call to his disciples to be free from selfishness, religious bigotry and spiritual inertia ... Guru Gobind bound the Sikhs to a particular necessity, and so that they are never forgetful of it he imprinted it in their hearts by name, attire, ritual and several other means.’

Tagore bemoaned the outcome of Sikh history. Like a river it had issued from a snowy mountain peak, but instead of making its way to the ocean it has gone meandering in the sand.

We know that this reading of Sikh history did not at all go down well with intellectuals and historians, Sikh or non-Sikh, except for Jadunath Sarkar who printed its English version in The Modern Review in 1911. What is of more immediate interest is what caused Tagore’s shift from his earlier admiration for Guru Gobind Singh. His disillusion with karma bereft of dharma must have come from the excesses and the communally exclusive nature of the Swadeshi and Boycott movements in Bengal, keeping the Bengal Muslims at bay and causing Hindu-Muslim riots. He himself had been part of these movements but soon withdrew. The ground was getting ready for his first political novel Ghare-Baire (1916: The Home and the World) which would draw no less fleck than the essay on Sikh history. It was a coincidence, yet perhaps no coincidence, that he would write his Nationalism lectures the same year in Japan that were not without a bearing on nationalism or nationalisms in India.

Jallianwala Bagh might have been anywhere in India and Tagore would have protested, but it being in Amritsar might have had an extra association for him. Yet the estrangement caused by the Sikh history essay went on for over two decades. Eventually during his visit to Lahore in 1935 things cleared up. Tagore addressed the Fifth Punjab Students’ Conference, read his poetry at the YMCA, had a warm reception from the local Sikh leaders, visited a Gurudwara, and reportedly issued a press statement confirming his regard for Sikhism. And it was on his return to Kolkata that he wrote his sixth and last Sikh poem, the one on Nehal Singh’s martyrdom.

[All translations from the Bengali are mine. Special acknowledgement: Professor Harjeet Singh Gill.—A.D.]

Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore visited Sikh temple during Vancouver visit

by CHARLIE SMITH

Source:-Sikhnet

BENGALI POET, ESSAYIST, and songwriter Rabindranath Tagore was a literary giant of the early 20th century, becoming the first non-European ever to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

And according to local cultural historian Naveen Girn, he visited the West 2nd Avenue Sikh temple when he visited Vancouver in 1929. Girn, research curator of the Surrey Art Gallery, told the Georgia Straight that while Tagore was at the temple (which is now on Ross Street), a photograph was taken of him surrounded by local admirers.

"The community knew he was coming," Girn revealed. "They brought together different community leaders—some from the island, and from Vancouver, and also Reverend [Charles Freer] Andrews."

Andrews, an Anglican priest, was a supporter of South Asians' right to vote and the Indian independence movement. He was a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi and was portrayed in Richard Attenborough's biopic of the Indian independence leader.

Tagore was aware of Ghadar activists

This year marks the centenary of Tagore winning the Nobel Prize in 1913. It's also the 100th anniversary of the creation of the Ghadar party of Indian independence activists along the west coast of North America. Several went back to India to support an armed struggle to try to force the British out of India.

"They passed articles by Tagore, too," Girn said. "They were very proud of him because he was a Nobel laureate."

The following year, Canadian immigration officials refused to allow more than 350 South Asian passengers on the Komagata Maru to disembark in Vancouver. The ship was sent back to India, where several were shot by British soldiers.

Tagore renounced his knighthood in 1919 after British Brig.-Gen. Reginald Dyer oversaw the massacre of peaceful demonstrators at the Jallianwala Bagh Garden in Amritsar in 1919.

This official death toll was 379 and another 1,100 were reported wounded. To this day, Britain has refused to apologize for the mass shooting, which was depicted in Attenborough's film.

Nehru also dropped by the temple

The Hotel Vancouver hosted then-Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira (a future prime minister) when they visited Vancouver in November 1949.

"He came to Vancouver because he knew about the community here," Girn said. "He knew about the Komagata Maru; he knew about the Ghadar party. They had been sending him updates about what was happening in the community."

Girn said that Nehru also spoke at the West 2nd Avenue gurdwara during his visit.

"He talks in the speech about the assassination of Gandhiji [Mahatma Gandhi], partition, and how South Asians living in Canada need to take an active life in Canadian life and not to ghettoize themselves. So before [Pierre] Trudeau, he’s talking about this idea of multiculturalism and how people should live together."

When Tagore visited the Temple for the first time, he'd been in Vacouver for three days already.

Tagore adored Sikhism - didn't he suggest that the point of unity for Hindus and Moslems in a united, free India should be a common admiration the Sikhs - so if he did sleep in the basement of the gurdwara, it was by choice, a great spiritual poet's gesture of faith and love, an act of inspiration, not oppression...

The real story is that this man, born to great wealth gave it all away, then used his world-wide fame to make more money, and gave that away, too. If there was a colour-bar at the Hotel Van, it didn't exist for Tagore. He had immense cultural influence, and carried a massive moral power in the Commonwealth & Empire. Yet, he took most of the day on April 11, 1929 to make his way to the Temple to express his solidarity with the Sikh community of B.C..

He didn't "drop by". He spent his childhood summers away from Bengal in Amritsar, and he went to Temple every night. On West Second, he was welcomed like family, and he spoke to the assembled as family. He envisioned a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, democratic India. He knew that Sikhs got a raw deal in the Punjab and in Canada. He thought that the tenets of Guru Nanak provided the foundation, or a model for such a state.

Michael Puttonen

AUG 9-12, 2013