Guru ka Bagh

This article which outlines the story of the Historical 400 years old Guru ka Bagh in Ghukkevali village, of Tehsil Ajnala, District Amritsar, of Punjab, is an account of a major campaign, just one of the many struggles by the Sikhs in the early 1920s, to seek justice, in regaining control of their own houses of worship.

Many Gurdwaras had already been freed without much of a problem, but this one would prove to be a bigger hurdle. Ghukkevali village, which is located about 20 km from Amritsar, has two historic gurdwaras located close to each other. One commemorates the visit of Guru Arjan in 1585. The other, laid out on the site of a bagh (garden), which gave it its name, is associated with a visit from Guru Tegh Bahadur in 1664.

Like most Gurdwaras, the management of these two had passed, long ago, during mid 18th century, into the hands of mahants (abbots or caretakers) who belonged to the monastic order of Udasi Sikhs, an order started by one of Guru Nanak's sons. The order had once been closely associated with Sikhi with its members often spreading Sikhi at one time. When the brave Sikhs had prices on their heads, and the Sikh Warriors, were fighting against the Mughals, a period of chaos, and hardship, and also known as the period of Sikh Martyrdom, and the founding of the Sikh Misls, In the same period, the Mahants whose appearance was more like that of a Hindu Sadhu, were asked to take care of only some of the Gurdwaras, which were Nankana Sahib, Panja Sahib, Guru Ka Bagh, and some Gurdwaras, around Anandpur Sahib. After 1849, fall of the Sikh Kingdom of Punjab, the mahants had Started to, grown apart from the Sikh religion and had started including Corrupt rituals and ceremonies in the Gurwaras that Sikhs found beadabe (sacreligious). The grant of jagirs to such sacred places in the times of the 18th century Sikh misls and the days of the many 19th century Sikh kingdoms, as well as the offerings of the devotees had made the custodians wealthy men who had become accustomed to luxury. Many of them had, like the Hindu Priests who passed the 'ownership' of a Mandir down through their family, begun to think of themselves as the owners of the Gurdwaras, and made It like their House. At Guru-ka-Bagh, the Sikh reformers' capacity for suffering and their capacity for resistance was put to the test. Many Gurdwaras had been regained through peaceful resistance, this one would prove to be a far more challenging task.

The Mahant

In 1921, Sundar Das Udasi was the mahant of Guru ka Bagh. He was indifferent to his ecclesiastical duties and lived a dissolute life, squandering the resources of the gurdwara. In an attempt to save the shrine from being occupied by reformist Sikhs, he signed a formal agreement with them on 31 January 1921, promising to reform his ways and make a new start, as well as, agreeing to receive the rites of Khalsa initiation. He even agreed to serve under an eleven member committee appointed by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. However, seeing how the government was everywhere supporting the mahants in their efforts to retain the Gurdwaras, he repudiated part of the agreement and said that, though he had surrendered the gurdwara to the Shiromani Committee, the piece of land known as Guru ka Bagh attached to it was still his property.

Firewood for the Langar

He objected to the Sikhs cutting down trees on that land for firewood to be used in the Guru ka Langar. The police, willing to oblige him, on August 9, 1922 arrested first five Sikhs Bhai Santokh Singh Lashkari Nangal, Bhai Labh Singh Rajasansi, Bhai Labh Singh Matte Nangal, Bhai Santa Singh Massa(Nakodar) and Bhai Phula Singh on charges of trespass. These arrests were not madet on Sundar Das' complaint, but on a confidential report received by the police. The following day, the arrested Sikhs were hurriedly tried and sentenced six months of rigorous imprisonment. They were also fined 50 rupee each and FIR case number 1288. This sparked off the agitation, and the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee decided to daily send a batch of five Sikhs to chop firewood from the grove of trees, on the land of Gurdwara Guru ka Bagh and court arrest if prevented from doing so. So undeterred by the action of the government, the Sikhs continued the old practice of hewing wood from Guru-ka-Bagh for the daily requirements of the community kitchen.

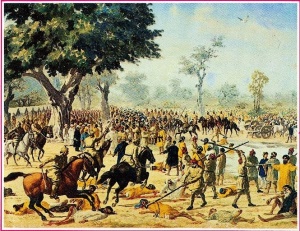

From 22 August 1922, police began to arrest the jathas on charges of theft, riot and criminal trespass. The arrests gave a boost to the movement as more and more Sikhs came forward to join the protest. On 25 August 1922, Amavas day, the gathering was so large that S.G.M. Beatty, Additional Superintendent of Police, ordered the police to disperse the Sangat by a lathi-charge.

Government terrorism and the Akali morcha

From about this time, as the process of arrests and convictions was proving of little effect, the police began trying a new technique of terrorizing the reformers. Those who came to cut firewood from Guru-ka-Bagh were beaten up in a merciless manner until they lay senseless on the ground. With their Dastars ripped off they were then dragged by their hair and left contemptuously discarded by the fields when the police thought they had enough beating to be totally subdued. The Sikhs suffered all this stoically and arrived, each day, in larger numbers to submit themselves to this beating.

On 26 August the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar issued warrants for the arrest of eight members of the executive of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. A council of action, headed by Teja Singh Samundri, now took over charge of the Akali morcha. The government banned the assembling of people at Guru ka Bagh, and police pickets were posted on roads and bridges to intercept volunteers coming into Amritsar. Yet jathas of black-turbaned Akalis chanting the sacred hymns reached the spot every day, only to be mercilessly beaten by the police until they fell to the ground. This happened everyday. Political leaders, social workers and reporters came to witness what was described as an ideal non-violent protest. A.L. Verges, an American cinematographer, prepared a film of the proceedings under the caption, "Exclusive Picture of India's Martyrdom."

More Sikhs arrive

From August 31, the number arriving to this site was raised to 100. Every day a batch of one hundred volunteers would start from the Akal Takht pledged to suffer their fate silently. The police would stop them on the way and slash them with heavy brass-bound sticks and rifle-butts. This punishment continued until the whole batch lay prostrate on the ground and none could stand any more. The Sikhs displayed unique powers of self-control and resolution, and bore the bodily torment in a spirit of complete resignation. None of them winced or raised a hand in defiance.

English missionary and educationist Rev. C.F. Andrews (1871-1940) who visited Guru ka Bagh and saw as he put it, "hundreds of Christs being crucified", gave a graphic description of the passive resistance of the Akalis. He sent to the Press a detailed report on what he witnessed on 12 September 1922:

The News reporter

". . .when I reached the Gurdwara (at Guru-ka-Bagh) itself, I was struck at once by the absence of excitement such as I had expected to find among so great a crowd of people..."

"Close to the entrance there was a reader of the Scriptures who was holding a very large congregation of worshippers silent as they were seated on the ground before him. In another quarter there were attendants who were preparing the simple evening meal for the Gurdwara guests by grinding the flour between two large stones. There was no sign that the actual beating had just begun and that the sufferers had already endured the shower of blows."

"But when I asked one of the passers by, he told me that the beating was now taking place. On hearing this news, I at once went forward. There were some hundreds present seated on an open piece of ground watching what was going on in front, their faces strained with agony. I watched their faces first of all, before I turned the corner of a building and reached a spot where I could see the beating itself. There was not a cry raised from the spectators, but the lips of very many of them were moving in prayer....."

the Gruesome events

"... There were four Akali Sikhs with their black turbans facing a band of about a dozen policemen, including two English officers. They had walked slowly up to the line of the police just before I had arrived and they were standing silently in front of them at about a yard's distance. They were perfectly still and did not move further forward. Their hands were placed together in prayer and it was clear that they were praying. Then without the slightest provocation on their part, an Englishman lunged forward the head of his lathi (staff) which was bound with brass. He lunged it forward in such a way that his fist which held the staff struck the Akali Sikh, who was praying, just at the collar-bone with great force. It looked the most cowardly blow as I saw it struck...."

"The blow which I saw was sufficient to fell the Akali Sikh and send him to the ground. He rolled over, and slowly got up once more, and faced the same punishment over again. Time after time one of the four who had gone forward was laid prostrate by repeated blows, now from the English officer and now from the [Indian] police who were under his control . The others were knocked out more quickly. "

Vicious acts by police

"On this and on subsequent occasions the police committed certain acts which were brutal in the extreme. I saw with my own eyes one of these police kick in the stomach of a Sikh who stood helplessly before him. It was a blow so foul that I could hardly restrain myself from crying out aloud and rushing forward. But later on I was to see another act which was, if anything, even fouler still. "

"For when one of the Akali Sikhs had been hurled to the ground and was lying prostrate, a police sepoy stamped with his foot upon him, using his full weight; the foot struck the prostrate man between the neck and the shoulder ..."

Nobility of the Sikhs

"The vow they had made to God was kept. I saw no act, no look, of defiance. It was true martyrdom for them as they went forward, a true act of faith, a true deed of devotion to God."

"They believe intensely that their right to cut wood in the garden of the Guru was an immemorial religious right, and this faith of theirs is surely to be counted for righteousness, whatever a defective and obsolete law may determine or fail to determine concerning legality."

"The brutality and inhumanity of the whole scene was indescribably increased by the fact that the men who were hit were praying to God and had already taken a vow that they would remain silent and peaceful in word and deed...."

"There has been something far greater in this event than a mere dispute about land and property. It has gone far beyond the technical questions of legal possession or distraint. A new heroism, learnt through suffering, has arisen in the land. A new lesson in moral warfare has been taught to the world...."

"One thing I have not mentioned which was significant of all that I have written concerning the spirit of the suffering endured. It was very rarely that I witnessed any Akali Singh, who went forward to suffer, finch from a blow when it was struck. Apart from the instinctive and involuntary reaction of the muscles that has the appearance of a slight shrinking back, there was nothing, so far as I can remember, that could be called a deliberate avoidance of the blows struck. The blows were received one by one without resistance and without a sign of fear."

Beating stopped

Sir Edward Maclagan, Lt-Governor of the Punjab, visited Guru ka Bagh on 13 September 1922. Under his orders, the beating of the volunteers was stopped. Mass arrests, imprisonments, heavy fines and attachment of properties were resorted to. At the government announcement that preparations were being made to accommodate ten thousand Akalis in gaols, the Sikhs stepped up their campaign. Jathas grew larger in size.

The government at last gave in. The offices of Sir Ganga Ram,. On November 16, 1922, he obtained the Guru-ka-Bagh land on lease from the mahant

In the first week of October, the Governor-General Lord Reading held discussions with the Governor of the Punjab at Shimla to find a way out of the impasse. The good offices of a wealthy retired engineer of Lahore, Sir Ganga Ram, were utilized to resolve the situation. Sir Ganga Ram acquired on lease, on 17 November 1922, 524 kanals and 12 marlas of the garden land from Mahant Sundar Das, and allowed the Akalis access to it. He also wrote to government that he required no police protection.

The Morcha succeeds

The government had the excuse not to interfere with the Sikhs who could now go unmolested to Guru-ka-Bagh to cut wood in the jungle for their Langar. The Sikhs' gain was not confined merely to the immediate point involved. The moral implication of the issue was far more important.

On 27 April 1923, Punjab Government issued orders for the release of the prisoners. Thus ended the morcha of Guru ka Bagh in which,. according to Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee records, 5,605 Sikhs went to jail.

However, the Sikh's trials had not ended. For protesting against the deposition of the Sikh Maharaja of Nabha, known for his sympathy with the Akalis and other nationalist elements, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee was, on October 13, 1923, declared an unlawful organization. Next morcha (front) in this war was Gurdwara Jaito at Nabha.

- Source:Encyclopaedia of Sikhism - Harbans Singh

External Links

The above article with thanks to: