Bhagat Singh Thind

Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind, Ph.D, (3 October 1892 - 15 September 1967) was an Indian American Sikh writer and lecturer on "spiritual science" who was involved in an important legal battle over the rights of Indians to obtain U.S. citizenship.

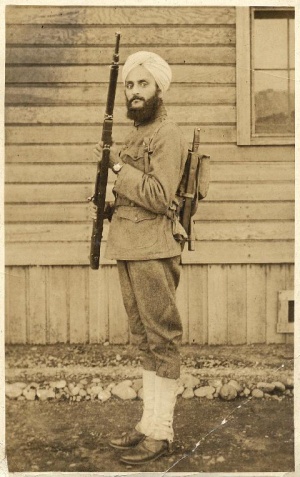

Today as Sikhs around the world have been attacked, because of ignorant (lit. those who do not know) people, or because of people who are ignorant of the suffering of the Sikhs at Muslim hands, which in numbers of dead makes 9/11 seem like a small incident, Dr. Thind accomplished what may seem like a small thing compared to his other accomplishments. Today as Khalsa Sikhs fight for their right to wear a beard or turban, not just in France, but in the US military forces (A right won! [1])- they can look at the 90 year old photo of the young recruit from the Punjab who did what others are still seeking the right to do today.

Just days before he turned 20 he had arrived in Seattle, Washington in 1913 on the day that every American holds near to his heart, the day when America had freed itself from the 'Shackles' of British tyranny; July 4th - Independance Day. Little could he imagine the part he would soon be playing in an early attempt to free his homeland from the yoke of the British. Leaving Seattle he worked his way through several lumber camps finally coming to 'rest' in Astoria, Oregon where a sizeable group of Sikhs had found success working in its huge lumber mill industry. He found work at the Hammond Lumber Company where he worked from 1914 to 1920, except for a brief interruption in the service of his new found country.

Only 4 months before his arrival in Astoria a new organization had been formed called the Hindoostan Association of the Pacific Coast. Its main objective was to liberate India from British rule, just as the Americans had done more than a century before.

That brief interruption

Though he was still an Indian citizen, Thind enlisted in the U.S. Army in May of 1918 fully aware that he might end up dying in the trenches of Europe; dying for a Country he wasn't even a citizen of. He had no way of knowing that the 'War to end all Wars' would end with an Armistice, signed November 11, 1918. At the camp he had gotten right to work, being appointed an acting Sergeant only days before he was mustered out only two days before the Armistice was signed, ending the war. He then sought the right to become a naturalized citizen, following a recent case in which the Supreme Court had ruled that, “Caucasians of Aryan decent” had the right to become an American citizen. At this time Indians were categorised as Caucasian by anthropologists.

Five years later in 1923, Dr. Thind's crucial Supreme Court case “United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind” was decided in favor of the United States, retroactively denying all Indian Americans citizenship for, as the court stated, not being Caucasian in "the common man's understanding of the term."

US citizenship background

In the annals of South Asians’ struggle for US citizenship, Bhagat Singh Thind’s fight for citizenship merits a prominent and certainly unique place in history. Thind’s first award of citizenship was rescinded only four days after it had been granted. Eleven months later, applying in a second state he received his citizenship a second time, but in an almost unbelievable move the US Immigration and Naturalization Service appealed his award of citizenship to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which sent Thind’s case to the next higher court for ruling. Thind valiantly fought his case all the way to the highest Court in the land, the Supreme Court.

Recently the court had ruled against a 'white' skinned Japanese, denying him citizenship because he was an “Asian” and not a “Caucasian” of Aryan decent. This earlier ruling seemed to guarantee Bhagat Singh Thind would finally win his right to be a US citizen, but incredibly his plea was denied. The Court sided with the Government's lawyers who were trying to uphold the so called purity of a “mythical white race”. Although Thind was of caucasian decent, the Government's lawyers had argued that skin color and blood of the “Pure white Aryan race” of their imagination had, in Thind's case, possibly been adulterated with darker and supposedly different blood of the Dravidian race. The verdict, United States v. Thind ensured that the rights and privileges of naturalization were reserved for the so called “White” Christians of Europe, Scandanavia and the middle East.

Sikhs called Hindoos

Since, even Indians coming to America at the turn of the Century still referred to India as Hindustan, it was no small wonder that many Americans, continued to use the old Mughal name for India. With rural education around the lumber mills being consisting of a one room school, Thind was probably far better educated than most of his fellow workers who knew little to nothing about Budhism, Sikhism and Hinduism. Only America's educated elete; scientists, writers and their highly educated readers had delved into ancient Hindu texts, knew anything about India, its religions and history. A Sikh by faith, Bhagat Singh Thind preserved his religious beliefs and practices, keeping his beard, long hair on his head he also wore a turban. *See footnote

With opportunities for a higher education limited in the Punjab, Bhagat Singh Thind had come to the US in 1913 to pursue a higher education in an American university. A career in Law was his dream, but in order to be a lawyer, he would have to become an American citizen. After landing in Seattle he worked his way from one lumber company to the next finally finding a job at a Lumber Company in Astoria, Oregon, where he worked for four years to earn money for his education, even as he continued to send money home to support his dad and pay for his brother's wedding. Reading his correspondence with his family, one can see that for many months he often worried if the funds had been received or if his father was even speaking with him. It looked as if his plans for school might be delayed for many months when on July 22, 1918, he was drafted into the US Army to fight in World War I. Apparently better educated than his fellow recruits or, perhaps, with his years of listening to tales of the martial exploits of his ancestors, he was just recognized as a natural leader of men, whatever the reason, on November 8, 1918, Bhagat Singh, still wearing his turban, was promoted to the rank of acting Sergeant.

Less than a month later the war ended November 11, 1918. Two days later, acting Sergeant Bhagat Singh received an “honorable discharge” (December 16, 1918) with his character noted as "excellent". The amazing thing, given that even today (2009) in Turkey, neither Sikhs or Muslims are allowed to wear turbans and in France turbans have been outlawed in schools and even the American army will not allow Sikhs to wear a turban, is that in 1918 when fear of diseases in the trenches on the European front, had resulted in new recruits being shaved and having all their hair trimmed almost to their scalps, is that Singh managed to be, perhaps, the only man to serve in the U.S. Army (basic traning program) with his beard, long hair and turban respected and intact. It would be interesting to know if he was ever even asked to wear a helmet. [Rashmi Sharma Singh: Petition for citizenship filed on September 27, 1935, State of New York].

At the time U.S. citizenship conferred many rights and privileges but only “free white men” were allowed to make use of them all. Declared un white many Indians especially could not marry a white woman of certain European ancestory. That particular exception was due to the efforts of powerful 'bigots' who had influenced lawmakers in many states to prevent people of African decent from marrying so called “white Christian women” of Eastern European or Latin American decent. 1. In the United States, many anthropologists used Caucasian as a general term for "white.” Indian nationals from the north of the Indian Sub-Continent of Aryan decent were also considered Caucasian. Thus, several Indians had been granted US citizenship in different states. Thind also applied for citizenship from the state of Washington in July 1918.

Becomes US Citizen Second time

He received his citizenship certificate on December 9, 1918 wearing military uniform as he was still serving in the US army. However, the Immigration and Naturalization Service did not agree with the district court granting the citizenship. Thind’s citizenship was revoked in four days, on December 13, 1918, on the grounds that he was not a “free white man.” Thind was trusted by the US to be a soldier in the army and had all the rights and privileges like any “white man.” He was worthy of trust to defend the US but his color stood in his way for the US to trust him for citizenship.

Thind was disheartened but was not ready to give up. He applied for citizenship again from the neighboring state, Oregon on May 6, 1919. The same Immigration and Naturalization Service official who got Thind’s citizenship revoked first time, tried to convince the judge to refuse citizenship to a “Hindoo” from India. He even brought up the issue of Thind’s involvement in the Gadar Movement, members of which campaigned actively for the independence of India from the British Empire. Judge Wolverton, believing Thind, observed, “He (Thind) stoutly denies that he was in any way connected with the alleged propaganda of the Gadar Press to violate the neutrality laws of this country, or that he was in sympathy with such a course. He frankly admits, nevertheless, that he is an advocate of the principle of India for the Indians, and would like to see India rid of British rule, but not that he favors an armed revolution for the accomplishment of this purpose.” The judge took all arguments and Thind’s military record into consideration and declined to agree with the INS. Thus, Thind received US citizenship for the second time on November 18, 1920.

Gadar Movement

The Immigration and Naturalization Service had included Thind’s involvement in the Gadar Movement as one of the reasons for the denial of citizenship to him. Gadar which literally means revolt or mutiny, was the name of the magazine of Hindustan Association of the Pacific Coast. The magazine became so popular among Indians, that the association itself became known as the Gadar party.

The Hindustan Association of the Pacific Coast was formed in 1913 with the objective of freeing India from the British rule. The majority of the supporters and members were from the Punjabi community who had come to the US for better economic opportunities. They were unhappy with racial prejudice and discrimination against them. Indian students, who were welcomed in the universities, also faced discrimination in finding jobs commensurate with their qualifications, on graduation. They attributed prejudice, inequity and unfairness to their being nationals of a subjugated country. Har Dyal, a faculty member at Stanford University, who had relinquished his scholarship and studies at Oxford University, England, provided leadership for the newly formed association and channelized the pro-Indian, anti-British sentiment of the students for independence of India.

Soon after the formation of the Gadar party, World War I broke out in August, 1914. The Germans, who fought against England in the war, offered the Indian Nationalists (Gadarites) financial aid for arms and ammunition to enable Indian volunteer fighters to expel the British from India while the British Indian troops would be busy fighting war at the front. The Gadarite volunteers, however, did not succeed in their mission and were taken captives upon reaching India. Several Gadarites were imprisoned, many for life, and some were hanged. In the United States too, many Gadarites and Germans who supported Gadar activities, were prosecuted in the San Francisco Hindu German Conspiracy Trial (1917-18) and some were convicted for varying terms of imprisonment for violating the American Neutrality Laws.

Case sent to Higher Court

Thind like many other Indian students had joined the Gadar movement and actively advocated independence of India from the British Empire. Judge Wolverton granted him citizenship after he was convinced that Thind was not involved in any “subversive” activities. The Immigration and Naturalization Service appealed against the judge’s decision to the next higher court – the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which sent the case to the US Supreme Court for ruling on the following two questions:

- "1. Is a high caste Hindu of full Indian blood, born at Amrit Sar, Punjab, India, a white person within the meaning of section 2169, Revised Statutes?"

- "2. Does the act of February 5, 1917 (39 Stat. L. 875, section 3) disqualify from naturalization as citizens those Hindus, now barred by that act, who had lawfully entered the United States prior to the passage of said act?"

Section 2169, Revised Statutes, provides that the provisions of the Naturalization Act “shall apply to aliens, being free white persons, and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.”

In preparing briefs for the Ninth Circuit Court, Thind’s attorney argued that the Immigration Act of 1917 barred new immigrants from India but did not deny citizenship to Indians who were legally admitted like Thind, prior to the passage of the new law. The purpose of the Immigration Act was “prospective and not retroactive.”

Attorney faces Racist Laws

Thind’s attorney gave references of previous court cases of some Indians who were granted citizenship by the lower federal courts which considered Indians as Caucasians and hence eligible for citizenship. (U.S. v. Dolla 1910, U.S. v. Balsara 1910, Akhay Kumar Mozumdar 1913, Mohan Singh, 1919). In 1922, in the case of a Japanese immigrant, US vs. Ozawa, the highest court, the U.S. Supreme Court officially equated “white person” with “a person of the Caucasian race”. Judge Wolverton, in granting citizenship to Thind, said, “The word “white” ethnologically speaking was intended to be applied in its popular sense to denote at least the members of the white or Caucasian race of people.”

Thind was convinced that based on Ozawa's straightforward ruling of racial specification and many similar previous court cases, he would win in the fight and his winning will open the doors for all Indians in the United States to obtain US citizenship. Little did he know that the color of his skin would become the grounds for denial of the right of citizenship by the highest court in the US.

White and Caucasian deemed different

Justice George Sutherland of the United States Supreme Court delivered the unanimous opinion of the court on February 19, 1923, in which he argued that since the "common man's" definition of “white” did not correspond to "Caucasian", which Indians were, they could not be naturalized. Thus the Judge, giving his verdict, said, “a negative answer must be given to the first question, which disposes of the case and renders an answer to the second question unnecessary, and it will be so certified.”

Shockingly, Justice Sutherland, the same judge who had equated Whites as Caucasians in US vs.Ozawa, pronounced that Thind though Caucasian, was not “White” and thus was ineligible for US citizenship. The judge apparently decided the case under the prevailing pressure by the forces of prejudice, racial hatred and bigotry, not on the basis of precedent that he had established in a previous case.

The Supreme Court verdict shook the faith and trust of many Indians in the American system of justice. The economic impact for land and property owning Indians was devastating as they again came under the jurisdiction of the California Alien Land Law of 1913 which restricted ownership of land by persons ineligible for citizenship. Some Indians had to liquidate their land holdings at dramatically lower prices. America, the dreamland, did not offer the dream they had come to realize.

Thind's citizenship revoked again!

Thind's citizenship was revoked and the INS issued a certificate in 1926 canceling his citizenship for a second time. The Immigration and Naturalization Bureau also initiated proceedings to rescind American citizenship of Indians and from 1923 to 1926, citizenship of fifty Indians was revoked. The Barred Zone Act of 1917 had already prevented fresh immigration of Indians. The continued shadow of insecurity and instability compelled some to go back to India to anchor their lives with their families and familiar environment. The Supreme Court decision further lead to the decline in the number of Indians to 3130 by 1930. [From India to America; Garry Hess, p 31]

Justice at Last

Probably, there was little sympathy for “Hindoo Thind” being denied his rights, but treating a US Veteran, even if he was “Indian Vet Bhagat Thind” poorly, rubbed many Americans the wrong way. Thus in 1935, the 74th congress passed a law allowing citizenship to US Veterans of World War I, even those from the 'barred zones'. Dr. Thind finally received his U.S. citizenship through the state of New York in 1936, taking oath for the third time to become an American citizen. This time, no official of the INS dared to object or appeal against his naturalization.

Thind had come to the US for a higher education and to “fulfill his destiny as a spiritual teacher.” Long before his arrival in the US or of any other religious teacher or yogi from India, American intellectuals had shown keen interest in Indian religious philosophy. Hindu sacred books translated by the English missionaries had made their way to America and were the “favorite text” of many members of the Transcendentalists’ society which was started by some American thinkers and intellectuals who were dissatisfied with spiritual inadequacy of the Unitarian Church. The society flourished during the period of 1836-1860 in the Boston area and had some prominent and influential members including author and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), poet Walter Whitman (1819 – 1892), and writer Henry David Thoreau (1817-62).

Emerson had read Hindu religious and philosophy books including Bhagvad Geeta, and his writings reflected influence of Indian philosophy. In 1836, Emerson expressed "mystical unity of nature" in his essay, "Nature." In 1868, Walt Whitman wrote the poem "Passage to India." Henry David Thoreau had considerable acquaintance of Indian philosophical works. He wrote an essay on "Resistance to Civil Government, or Civil Disobedience" in 1849 advocating non-violent resistance against unethical government laws. Many years later, in 1906, Gandhi Ji adopted similar methodology, satyagraha, or non-violent protest to defy the law to gain Indian rights in South Africa. Gandhi Ji quoted Thoreau many times in his paper, Indian Openion.

Background of Indians in the US

In 1893, Vivekananda came to Chicago to represent Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions. He was fluent in English, spoke very eloquently and made a lasting impact on the delegates. For four years, he lectured at major universities and retreats and generated significant interest in yoga and Vedantic philosophy. He also started Vedantic centre in New York City to promote and propagate Vedantic philosophy. In 1897, he published his book “Vedanta Philosophy --lectures on Raja Yoga and other subjects.” The first part of his book included lectures to classes in New York and second part contained translation and commentary of “Patanjali.” [Pradhan:India in the United States]

Swami Vivekananda’s constant teaching, lecturing and addressing retreats for four years increased the number of Americans who became receptive to learn about India, Hindu religion and philosophy. More publishers brought out books to meet the growing interest of the American people. Scribner, Armstrong and Co. published India and Its Native Princes, a 580 pages illustrated coffee table book. C.H. Forbes-Lindsay of Philadelphia published a beautifully hard bound book “India – Past and Present” in two volumes in October, 1903. The Yogi Publication Society of Chicago published many books such as The Hindu-yogi science of breath (1905), A Series of Lessons in Raja Yoga (1906), Bhagavad Gita (1907), etc.

After Swami Vivekananda had left America, some other religious leaders came to fill the void. In 1920, Paramahansa Yogananda came as India’s delegate to international congress of religious leaders in Boston. The same year, he established Self-Realization Fellowship and for the next few years, he continued to spread his teachings on yoga and meditation in the East coast. In 1925, he established an international headquarters for Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles. He traveled widely and lectured to capacity audiences in many of the largest auditoriums in the country such as New York's Carnegie Hall. (www.yogananda-srf.org)

A few years prior to Yogananda, Bhagat Singh Thind had started delivering lectures in Indian philosophy and metaphysics.

Thind contribution to change in US attitudes

Thind, during his early life, was influenced by the spiritual teachings of his father whose “living example left an indelible blueprint in him.” During his formative years in India, he read the literary writings of American authors Emerson, Whitman, and Thoreau and they too had deeply impressed him. After graduating from Khalsa College, Amritsar, Punjab, and encouraged by his father, he left for Manila, Philippines where he stayed for a year. He resumed his journey to his destination and reached Seattle, Washington, on July 4, 1913.

Thind had gained some understanding of the American mind by interacting with students and teachers at the university and with common people by working in lumber mills of Oregon and Washington during summer vacations to support himself while at UC Berkeley. Thus, his teaching included the philosophy of many religions and in particular that contained in Sikh scriptures. During his lectures, discourses and classes to Christian audience, he frequently quoted Vedas, Guru Nanak, Kabir, etc. He also made references to the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau to which his American audience could easily relate to. He gave new “vista of awareness” to his students throughout the United States and was able to initiate “thousands of disciples” into his expanded view of reality – “the Inner Life, and the discovery of the power of the Holy Nãm.” He never converted or persuaded any of his students to become Hindu or Sikh but generously shared India’s mystical, spiritual and philosophical treasures with them.

Thind who had earned a Ph.D, became a prolific writer and was respected as “spiritual guide.” He published many pamphlets and books and reached “an audience of at least five million.” The list of his books include Radiant Road to Reality, Science of Union with God , The Pearl of Greatest Price, House of Happiness, Jesus, The Christ: In the Light of Spiritual Science (Vol. I, II, III), The Enlightened Life, Tested Universal Science of Individual Meditation in Sikh Religion, Divine Wisdom in three volumes. see Thind's Website for more details

In "RADIANT ROAD TO REALITY", Dr. Thind reveals an exact science showing the seeker how to connect the individual soul with its Universal Creator. "There are many religions, but only one Morality, one Truth, and one God. The only Heaven is one of conscious life and fellowship with God," explains Dr. Thind. He wrote, JESUS, THE CHRIST: In the Light of Spiritual Science in three volumes for those, “Who have freed themselves of orthodox religious thinking. The books serve as a springboard to greater spiritual heights, wherein we appreciate more than ever the message of the Sat Gurus, the Saviors, the Avatars, the Christs, of whom Jesus Christ was one.”

Thind dies suddenly

Thind was working on some books when suddenly he died on September 15, 1967. He was born on October 3, 1892, thousands of miles away in the village of Taragarh, tehsil Jundiala, district Amritsar, in the state of Punjab, India. He was survived by his wife, Vivian, whom he had married in March, 1940, daughter, Rosalind and son, David, to whom several of his books are dedicated.

Thind never established a temple, Gurdwara or a center for his followers but lived for a long time in the hearts of his numerous followers. David Thind, long after his father’s death, has established a website www.Bhagatsinghthind.com to propagate the philosophy for which Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind spent his entire life in the US. He has also posthumously published two of his father’s books, Troubled Mind in a Torturing World and their Conquest, and Winners and Whiners in this Whirling World and is working on some others.

Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind said, “You must never be limited by external authority, whether it be vested in a church, man, or book. It is your right to question, challenge, and investigate.” Dr. Thind lived his life by that statement. He was a man of indomitable spirit and waged a deeply effective struggle for citizenship. He extended the boundaries of his fight by challenging the forces of race and color. Unfortunately, even the highest US court could not rise above the low level of skin color.

The above article is based on an article by Inder Singh, chairman of the Indian American Heritage Foundation, president of Global Organization of People of Indian Origin (GOPIO International), former president of NFIA and founding president of the FIA of Southern California. He can be reached by email at:

- [email protected] or by telephone at 818 708-3885.

Footnote: Even at a Sikh owned bookstore, perhaps the best source of books on Sikhism in America - just down the street from Berkeley this [user/reader/sometimes editor] of Sikhiwiki purchased a book titled, “Learning to Speak Hindustani”. Of all my books on Punjabi, Hindi and Urdu it explains the language and its structural differences from English the best.

See also

- United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind

- Komagata Maru

- Sikh Military

- North America

- Sikhism by country

- Sikhism in the USA

- Sikhism in Canada

External Links

Check out the web site dedicated to Bhagat Singh Thind for more information. See: Thind's Website for more details

- Short Documentary Clip of Dr. B.S Thind

- See Wikipedia article on Bhagat Singh Thind for more information